The Apocalyptic Chant Of Alex McDermott

Captain Jack Hoyle (retired)

I want to write history that ordinary people will find interesting … (to) give Australians a better understanding of themselves, through differentiating truth from legend in the critical events of history.

Alex McDermott

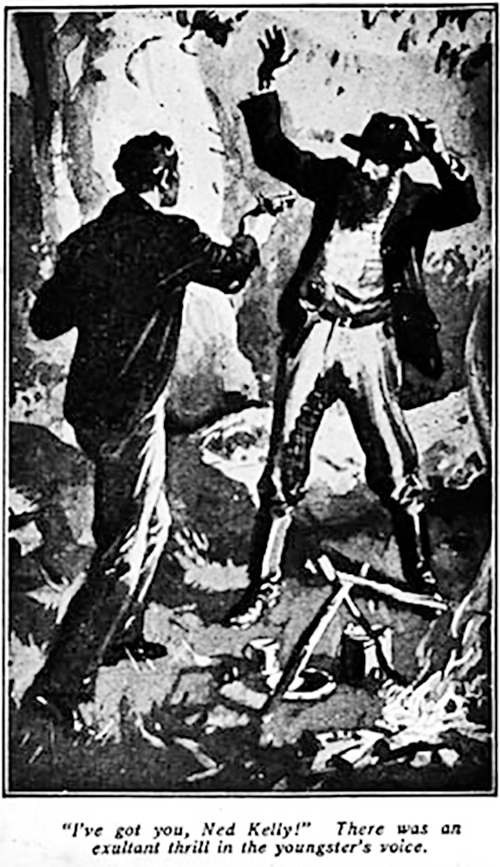

In Alex McDermott’s introduction to his book The Jerilderie Letter he names it ‘The Apocalyptic Chant of Edward Kelly’ Mr. McDermott claims the letter ‘tells the story of a violent man living a violent life’ but concedes ‘(Kelly) articulates a highly acute sense of honour and integrity’. This statement defines the debate that has raged since 1878 and helps explain the enduring fascination of Ned Kelly. When asked by Tony Robinson “Was Ned Kelly a hero or a villain?” Mr. McDermott replied “A heroic villain”

Mr. McDermott is described as a Kelly expert on television and in the press, as ‘Project Historian Archaeological Dig at Glenrowan Inn’ and ‘Research Scholar La Trobe University.’ His academic reputation is impressive. His appearance as main speaker at the 2009 Beechworth Kelly Weekend will be another addition to his Kelly Curriculum Vitae and should add considerable colour and movement to the proceedings.

Mr. McDermott’s reputation is based on his La Trobe University thesis on the Cameron and Jerilderie Letters, his annotated book of the Jerilderie Letter, combined with his book reviews and media appearances.

In his review of Peter Carey’s novel The True History of The Kelly Gang Mr. McDermott reveals his main source of research ‘I was lucky enough to come across the meticulous study by Douglas Morrissey Selector’s, Squatters and Stock Thieves: A Social History of Kelly Country. This work shows conclusively that the wide-scale stock theft then current in the region was largely specific to a close-knit group of people who were not representative of the local selector population.’

In his review of Peter Carey’s novel The True History of The Kelly Gang Mr. McDermott reveals his main source of research ‘I was lucky enough to come across the meticulous study by Douglas Morrissey Selector’s, Squatters and Stock Thieves: A Social History of Kelly Country. This work shows conclusively that the wide-scale stock theft then current in the region was largely specific to a close-knit group of people who were not representative of the local selector population.’

Mr. McDermott then dismisses the decades of research by Ian Jones and calls John McQuilton’s book The Kelly Outbreak 1878 – 1880 – The Geographical Dimensions of Social Banditry ‘impressively titled’ but flawed in its argument ‘that the outbreak was the expression of the deep seated antagonism between rich squatter and poor selector in the region.’

Mr. McDermott writes that only Morrissey ‘cuts right across and undermines the prevailing orthodoxies of Kelly studies’ and states that the thesis has never been able to find a publisher. As Mr. McDermott complains, Morrissey’s work is hard to find, but reading Morrissey’s October 1978 article in Volume 18 #71 Historical Studies of Australia and New Zealand reveals his view of the Kelly story.

Morrissey’s thesis is that ‘(Sympathy) may well have been exaggerated. As well as sympathy, there was, though most writers are reluctant to discuss it, fear and intimidation. Ned Kelly seems as a matter of course to have threatened to shoot anyone who revealed his whereabouts to the police. Jacob Wilson, a selector who did pass information about the Kellys to the police, was constantly harassed and menaced by active sympathisers, so much so that he sold his selection and left the district.’

Wilson felt safe enough to stay at Greta until he claimed to the Royal Commission that he was chased out of the district by Tom Lloyd’s brother Paddy on the 16th of July 1880. Constable Charles Gascoigne disagreed with his testimony referring to the man as ‘Holy Wilson’ and said ‘I believe the statement made is incorrect. He used to get frightened by a young man named Cass, living a hundred yards off. I never saw signs of anything, and I was round night and day.’ (RC Question: 9825) McQuilton writes ‘Wilson had been a heavy drinker who had forfeited his land to Benalla’s shopkeepers because of debts’ Justin Corfield in The Ned Kelly Encyclopedia states that he had to pay debts to the publican De Boos owner of the North Eastern Hotel where Joe Byrne visited when planning the bank raid on Euroa.

Wilson felt safe enough to stay at Greta until he claimed to the Royal Commission that he was chased out of the district by Tom Lloyd’s brother Paddy on the 16th of July 1880. Constable Charles Gascoigne disagreed with his testimony referring to the man as ‘Holy Wilson’ and said ‘I believe the statement made is incorrect. He used to get frightened by a young man named Cass, living a hundred yards off. I never saw signs of anything, and I was round night and day.’ (RC Question: 9825) McQuilton writes ‘Wilson had been a heavy drinker who had forfeited his land to Benalla’s shopkeepers because of debts’ Justin Corfield in The Ned Kelly Encyclopedia states that he had to pay debts to the publican De Boos owner of the North Eastern Hotel where Joe Byrne visited when planning the bank raid on Euroa.

But Mr. McDermott warns us against the work of McQuilton and Corfield as they have been ‘reliant on Eric Hobsbawm’s theory of social banditry.’ In his review of Carey’s novel he states ‘Carey makes this mistake, as have Jones, Seal and McQuilton before him.’ Of Corfield’s mammoth tome he credits Corfield with producing a book whose ‘marvels are manifold. No other previously published work aims so high and achieves so much.’ But warns the reader that Cornfield too ‘has been bewitched, at an early age I think.’ Sympathy does not an encyclopedia make, and Mr. McDermott may have a valid point. Mr. McDermott then writes ‘This is not a view to which I subscribe. On the personal level, it ignores the darker malevolence, the propensity for violence (both in word and deed), the wild manias, the sheer hubris – as much a part of Kelly’s sense of status and prestige as the honour and eloquence.’

Douglas J Morrissey recommends Weston Bate’s essay Kelly and His Times as ‘the most valuable’. Bates writes ‘Kelly based his picture of society on the wrong done to the small man. There seemed to be one law for the rich, like Whitty and Burns, and one for the poor in this lovely country’. He also states ‘A man who was as eloquent on a horse as was Ned Kelly became dramatically free. His horse was a symbol to him of his freedom from the difficult path of trying to be a bona fide selector under conditions in which most bona fide selectors without capital were trampled on.’ Bates must have been bewitched too. But Morrissey warns ‘Bates almost certainly exaggerates.’

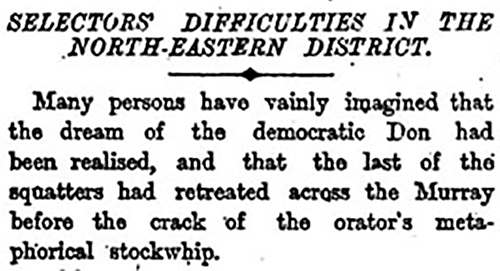

Ned Kelly talks much of the selector’s plight in his letters but Mr. McDermott places Kelly’s loyalties with ‘the thriving shanty culture’ rather than poor farmers. That Mrs. Kelly was charged but never convicted of selling sly grog to a police agent is well known, but hardly proves that the ‘vine covered hut’ of Kelly folk songs was a shebeen or an unlicensed pub. Only seven weeks after the Jerilderie letter’s delivery The Age published a report on Saturday March 29th 1879 entitled ‘Selectors Difficulties in the North–Eastern District’. The supposedly radical Age was anti-Kelly and saw no connection to Kelly’s statements when they wrote ‘It was at least supposed by the general community that the petty tyrannies and cunning devices of the pastoral fief-holders (squatters) had long been swept away, and that yeoman selectors were at liberty to go unimpeded and take up land wherever the Crown claimed ownership. But such is not the case.’

The Age states ‘Encouraged by the remoteness of the district from headquarters, the sparseness of population, the absence of newspapers, a pliant local land office, and Squatter Governments, all the old tyrannies and petty modes of harassing bona fide settlers that at one time held universal rule in Victoria has found a snug retreat in the North Eastern district.’ Squatter governments whose armies were the Police and the Land Office! The article reports on the conduct of the Beechworth Land Office ‘information regarding land is systematically withheld, or that wrong information is given; that surveys are delayed and made in a manner to be inimical to the selector. The doings of the squatters, the Land Office and the Shire Council are so intermixed that it is not possible to separate them. They join together for one common purpose, and stand as a sign to the selectors that the rain (or reign) of misfortune is to descend on the yeoman settler.’ If The Age report is not as poetic as Ned Kelly’s words, it tells the same story.

The article refers to the Squatter Council of Towong and states ‘it was made apparent that the squatters in this district, to suit their own purpose, are in the habit of inverting the practice that obtains elsewhere, viz., that of closing the roads. Through and by the power vested in the shire council – composed of squatters, with two exceptions – they open roads through selections for no other purpose than that of annoying selectors and making their holdings valueless by reason of the high and low portions of the land being severed.’

The article refers to the Squatter Council of Towong and states ‘it was made apparent that the squatters in this district, to suit their own purpose, are in the habit of inverting the practice that obtains elsewhere, viz., that of closing the roads. Through and by the power vested in the shire council – composed of squatters, with two exceptions – they open roads through selections for no other purpose than that of annoying selectors and making their holdings valueless by reason of the high and low portions of the land being severed.’

The proud, manly Yeoman was English nostalgia for the men of the Elizabethan period before the ‘dark satanic mills’ had choked fair Mother England. The slum dwellers and convicts would be invigorated and rehabilitated by the fresh air and hard work in this new Arcadia. Ned Kelly might have been the ideal yeoman farmer but between the ‘shanty culture’ of Mr. McDermott’s thesis, the zealous work of the ‘squatter government’ and their officials and Kelly’s decision to engage in ‘wholesale and retail’ stock theft, such was not life.

Mr. McDermott claims that Kelly had ‘pivotal involvement in organized stock theft for a decade.’ Kelly was charged by that zealous official of the ‘squatter government’, Senior Constable Edward Hall, and imprisoned in October 1870 for 6 months, but was eventually released in February 1874. In what amounted to a three week holiday from prison, Hall interrupted Kelly’s return to society when he saw Kelly proudly riding Wild Wright’s fine, stolen horse.

Hall fired three shots but ‘the Colts patent refused’ as Ned states, then after having Kelly subdued and tied with rope, pistol whipped him ready for his trial and sentencing. Kelly’s release in 1874 and his years of honest work at sawmills and stone yards coupled with the end of Kelly’s ‘whole sale and retail’ business after the Fitzpatrick incident on April the 15th 1878 reduces that decade of horse stealing to a few years.

When Mr. McDermott debated Ian Jones with Tony Jones on ABC Lateline 9/04/2001 after the publication of his book he said “I would offer the contrary argument (to Ian Jones) there’s such a history of fear and climate of intimidation that Ned, amongst others, has managed to inculcate over the years.”

A sharp contrast to this view is found in the family history of Florence Cathcart whose book Pictures on my Screen tells of her grandmother Katie Doyle, who lived at Greta during the Kelly years. Grandma Doyle remembered seeing the Kelly children ‘in an old spring cart; they had chaff bags over their shoulders to keep out the rain and cold. Very gaunt, wild eyed, but proud and fierce did Mrs. Kelly look.’ ‘If the Kelly brothers were to be thought of as ‘wicked and dangerous men’ then ‘Part of the real truth was that some of the police were wicked too. This was the law that sought only to punish and never to rehabilitate.’

Katie Doyle also ‘when a girl danced with the dashing Sergeant Kennedy at Mansfield dances, and his photo is in our family album.’ The author writes that her grandfather ‘saw the body of the Sergeant being transported into the town, covered in gumtree boughs, but with legs, stiff in death, protruding from the end of the cart.’

Katie Doyle also ‘when a girl danced with the dashing Sergeant Kennedy at Mansfield dances, and his photo is in our family album.’ The author writes that her grandfather ‘saw the body of the Sergeant being transported into the town, covered in gumtree boughs, but with legs, stiff in death, protruding from the end of the cart.’

‘My little Grandma prayed for the police and the Kellys with impartial fervor.’

So we return to the beginning, the 130 year argument that will probably rage as long as there are Australians. Kelly’s story has from the beginning enthralled the entire world and the myth will keep evolving into the future. That is why Ned Kelly has been a major target of the ‘History Wars’, an attempt to rewrite, or wrestle Australian history from the perceived clutches of ‘left wing’ academics. Kelly seems to be perpetually on trial these days, but having been hanged by the neck until he was dead; it is still not enough punishment for his crimes. Kelly’s words still have a symbolic power that renders him more dangerous than we may realize.

By naming his introduction ‘The Apocalyptic Chant’ a sly reference to the 1978 movie ‘The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith’, based on the 1972 novel by Thomas Kenneally, ironically related to JJ Kenneally, an association with the main target of this ‘war’ – Aboriginal/Settler History – is cleverly made. Mr. McDermott may be aligned with this movement in his ‘violent’ and ‘malevolent’ reading of Ned Kelly, but he is a far superior and engaging writer than the usual ‘Ned Kelly was a murderous thug’ article that is printed regularly in the newspapers as part of the campaign to paint Kelly as a vengeful terrorist.

Mr. McDermott has enough scholarly rigour to admit that ‘I think he is one of the most extraordinary individuals we’ve had throughout the entirety of Australian history. For a native born Aussie growing up in the back blocks of colonial Victoria to come up with a document as powerful and viscerally affecting as the Jerilderie Letter – it could only have been produced by a truly extraordinary individual – and then he backs it up with his exploits as a bushranger. He really was extraordinary.’ And who would argue with that insightful statement?

With Mr. McDermott’s excellent knowledge and skilled writing it is to be hoped that he will one day produce a more detailed examination of the life of Ned Kelly. His review of Peter Carey’s novel The True History of the Kelly Gang was an informed examination of how Carey did not find the ‘true’ voice of Ned Kelly.

An articulate historian with an obvious interest in the Kelly saga will only help continue the interest in the Kelly enigma. A superficial reading of Kelly’s criminal record makes it easy to paint Kelly as a ‘malevolent’ violent man, but for every police report there is a statement such as James Ingram’s, Beechworth bookseller and a Police Magistrate for forty years: ‘I was well acquainted with Ned Kelly long before he took to the bush. He was, in his usual manner, of a quiet unassuming disposition – a polite and gentlemanly man. I would not have been afraid to have met Ned Kelly in the bush anywhere’.

Mr. McDermott should beware lest his research leads him to also become ‘bewitched’ by the ‘extraordinary’ Mr. Edward Kelly.

References

Alex McDermott The Jerilderie Letter The Text Publishing Company, 2001.

Douglas J Morrissey Ned Kelly Sympathisers Historical Studies Australia and New Zealand Vol 18, No 71. University of Melbourne. October 1978.

John McQuilton The Kelly Outbreak 1878 -1880 The Geographical Dimension of Social Outlawry Melbourne University Press, 1979.

Florence Cathcart Pictures on my Screen, Growing up in Kelly Country Spectrum Publications, 1989.

J.J. Kenneally The Inner History of the Kelly Gang The Kelly Gang Publishing Co Pty Ltd, 1969 Edition.