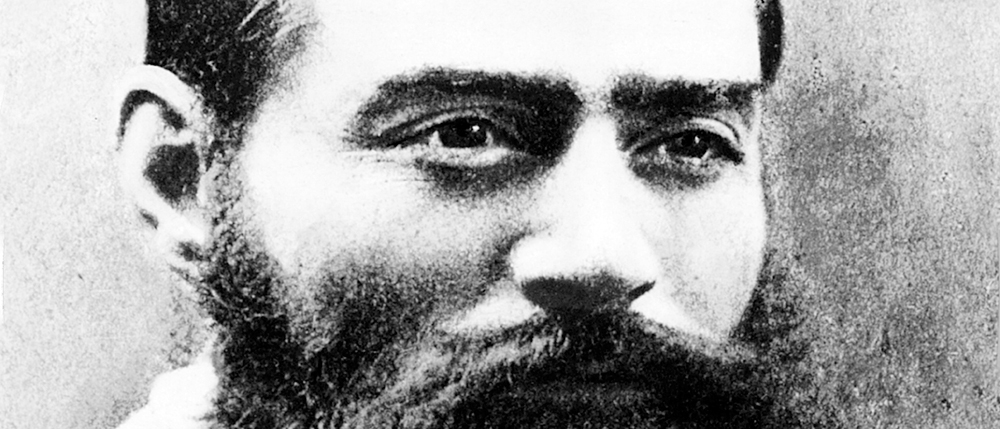

Like most outlaws Ned Kelly died young, being only twenty-five when he was executed. He was expert with a ‘running-iron’ on stolen, unbranded stock, and was a deadly accurate shot with revolver or rifle. Surprisingly articulate for a self-educated man, he was clannish, loyal to his friends and supporters, and had a sardonic sense of humour. He became an outlaw, hunted for almost two years before he was shot down and hanged. To the last, his mocking courage never deserted him and to be ‘as game as Ned Kelly’; came to symbolise, in Australian folk-language, heroism of a reckless, audacious nature.

Preface to a Legend

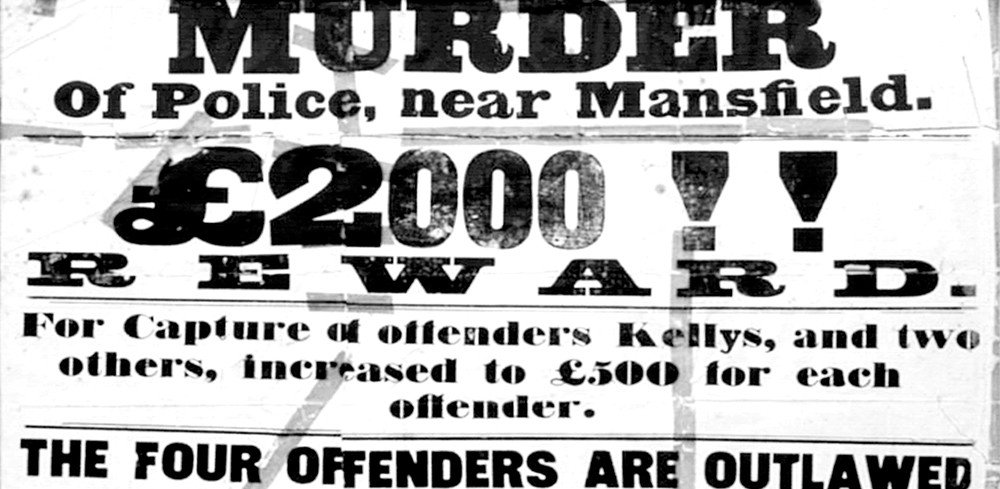

Ned was born in June 1855 to a proud Irish Catholic family whose resentment of the British set the precedent for his life. His short story is one that saw Ned and three mates take on corrupt police, greedy land barons and an ignorant government in a quest to change their world for the better. Wrongly accused, they survived a deadly shoot out with police in 1878 that saw Ned, his brother Dan, and their mates Joe Byrne and Steve Hart, outlawed with the largest reward ever offered in the British Empire – dead or alive.

Over the next eighteen months, the Kelly Gang held up two country towns and robbed their banks without firing a single shot, wrote numerous essays explaining their actions, and became folk heroes to the masses. Their grand plan to derail a special police train and declare a Republic of North East Victoria came to a fiery end in Glenrowan when they donned their famous but cumbersome armour against an overwhelming police force. By November 11, 1880 the era of the Kelly Gang drew to a close when Ned, after a brief trial, was hanged. Yet the legacy of his life and the chord he struck within a young Australia, unwilling to bend to injustice, saw Ned Kelly become Australia’s most enduring legend.

Far more than a folk hero, Ned Kelly has become one with the Australian spirit. Listed in the top one hundred of the world’s most influential Irish and arguably Australia’s best-known historical figure, our Ned truly deserves his place in the pages of history. As the subject for the world’s first feature film made in Australia in 1906, The Story of the Kelly Gang has been added to a United Nations heritage register, joining a list of fewer than two hundred items on UNESCO’s Memory of the World register, including the family archives of Swedish philanthropist Alfred Nobel and the official trial records of Nelson Mandela.

The Early Years

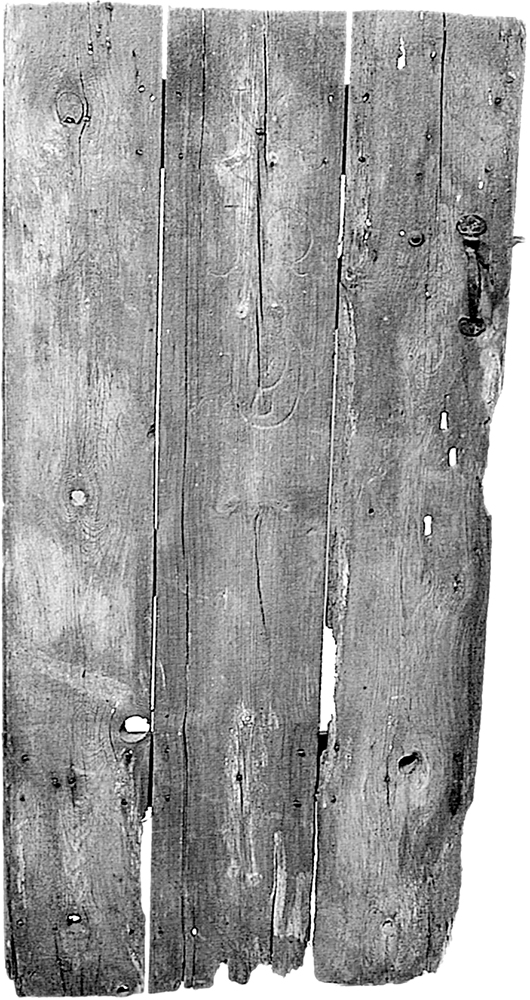

Young Ned Kelly’s initials (EK and two K’s) carved into the door of his grandfather’s forge at the Quinn homestead, Wallan. Also seen here are sample ‘burns’ of newly-made branding irons – the Q with a dropped tail and the later JQ. Image: Matt Deller

Young Ned Kelly’s initials (EK and two K’s) carved into the door of his grandfather’s forge at the Quinn homestead, Wallan. Also seen here are sample ‘burns’ of newly-made branding irons – the Q with a dropped tail and the later JQ. Image: Matt Deller

In 1841, Ellen and her six brothers and sisters arrived in Australia from County Antrim, Ireland. Her father, James Quinn, was a free settler who rented land for dairying in Brunswick upon their arrival. In the early 1850s they settled in Wallan near the Merri Creek. While at Wallan, James Quinn hired a young labourer, John ‘Red’ Kelly, fresh from Van Diemen’s Land.

Kelly had served a seven year sentence for stealing two pigs after being transported from Tipperary, Ireland. It was in Wallan that John met James’ daughter Ellen and they were to marry soon after at St. Francis’ Roman Catholic Church in Melbourne. John and Ellen Kelly lived with the Quinns after they were married and it was here that a young Ned Kelly carved his initials, an EK and two K’s, into the door of his grandfather’s forge.

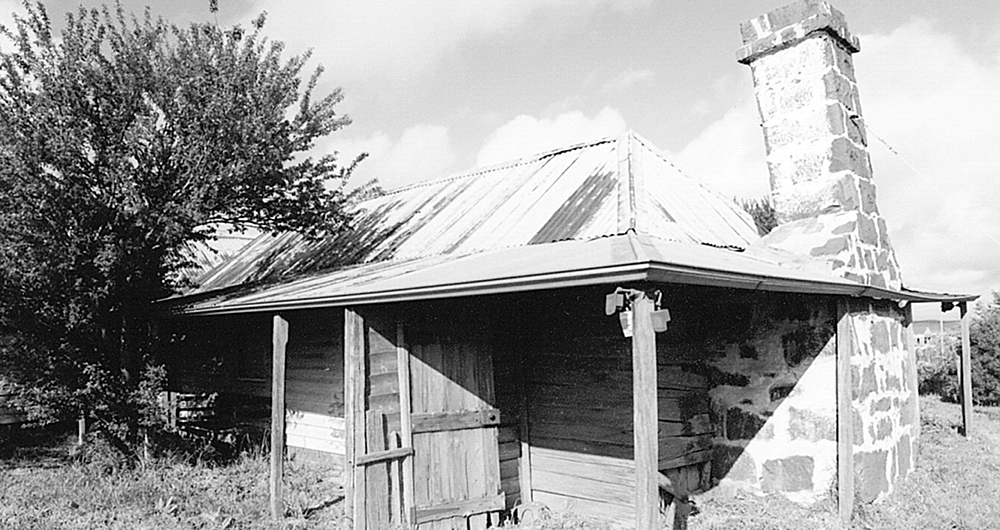

In 1854 the Kelly’s moved a short distance along the Hume Highway to Beveridge after ‘Red’ purchased twenty-one acres for seventy pounds – money he had managed to save from gold digging and horse-dealing. In January 1859, when his son Ned was nearly four years old, John Kelly built the family a timber cottage. It was a typical Irish style of cottage with an earthen floor and drainage running between rooms. Internally, there were only two rooms and there was no ceiling, while the bluestone chimney dominated the house.

By 1862, young Ned had started school in the little town’s new Roman Catholic Church. The two teachers, Thomas and Sarah Wall, also taught Ned’s sisters Annie, aged nine, and Maggie, aged six. A surviving description of Ned by schoolmate Frederick Hopkins states, ‘He was a tall active lad and excelled all others at school games.’ In six months, Ned had learned to read and write to second class standard, before ‘Red’ sold his farm in 1864 for eighty pounds.

Two of Ellen Kelly’s sisters married members of the Lloyd family and for many years the Kellys, the Quinns and the Lloyds made a formidable clan. John and Ellen Kelly had eight children: Mary, Annie, Ned, Maggie, Jim, Dan, Kate and Grace. After he sold Beveridge, ‘Red’ took the family eighty kilometres north to Avenel in a bid to avoid being caught up with his brother Jim, who was already up to his neck in the horse and cattle stealing and would soon be in trouble with the law. The Kellys thus shifted over the Great Dividing Range, a four day journey with stock, although a skilled horseman could cover the distance overnight.

Richard Shelton who was rescued by young Ned from Hughes Creek, Avenel. Two of Richard Shelton’s sons are still alive. A grandson, Ian ‘Bluey’ Shelton, was a famous Essendon footballer. Richard’s grateful parents, Esau and Margaret (seen in locket portraits), presented Ned with a handsome green silk sash. Image: Shelton Family

Richard Shelton who was rescued by young Ned from Hughes Creek, Avenel. Two of Richard Shelton’s sons are still alive. A grandson, Ian ‘Bluey’ Shelton, was a famous Essendon footballer. Richard’s grateful parents, Esau and Margaret (seen in locket portraits), presented Ned with a handsome green silk sash. Image: Shelton Family

It was here in 1865, a young Richard ‘Dick’ Shelton was nearly swept away in the flooded waters of Hughes Creek as he attempted to cross a fallen-tree-footbridge on his way to school. He was rescued by a ten-year-old Ned Kelly, who, without hesitation, jumped into the swollen waters fully clothed and paddled young Dick safely to the creek’s bank. The shivering youngsters made their way to the nearby Royal Mail Hotel which was owned by Dick’s parents, Esau and Margaret Shelton. The boys dried themselves by the fireplace and Esau lent Ned some clothes, while Dick retold the near fatal story.

The Sheltons rewarded Ned with an elaborate two hundred and twenty-one centimetre long, fourteen centimetre wide green silk sash complete with gold bullion fringes at each end. The colour chosen was symbolic of Irish heritage. It is also probable the Sheltons paid Ned’s father Red’s court fine allowing him to return to his family with an early release from the Avenel lockup where John ‘Red’ Kelly had been charged with stealing a calf from a Mr. Morgan.

While the charge of cattle stealing was dismissed, the charge of ‘unlawful possession of a hide’ was upheld and he was fined £25 or six months in gaol. Unable to pay the fine, Red was held at the Avenel lock-up instead of the far harsher Kilmore Gaol. This, more than likely, had something to do with the regard people held for his son Ned and his saving of the Shelton lad. Ned’s bravery may have won his father lenient treatment, a generous remission, and imprisonment in the local lock-up instead of a distant gaol, however, when ‘Red’ returned to the family in the first week of October 1865, he also returned to the bottle and, scarcely more than a year later, died of dropsy — an alcohol induced illness that bloats the body.

The sudden death of his father meant that Ned had to leave school at the age of twelve. John ‘Red’ Kelly was buried at the Avenel Cemetery in December 1866 and Ned Kelly, at the age of eleven-and-a-half, stepped into his father’s shoes and left his school life behind. The loss of the family breadwinner was a severe blow to the family but Mrs Kelly, a widow at age thirty-three with seven children. was a determined woman. She moved her family to a slab hut on Eleven Mile Creek, not far from Benalla and halfway between Greta and Glenrowan, an area which today is still referred to as ‘Kelly Country’.

The green silk sash with a bullion fringe became one of Ned’s most treasured possessions and he wore it during his Last Stand. After Ned’s capture, Dr Nicholson of Benalla removed the sash while treating his wounds and kept it as a souvenir. Dr Nicholson’s daughter donated the sash in 1973. Today it is on display, still stained with Ned’s blood.

The green silk sash with a bullion fringe became one of Ned’s most treasured possessions and he wore it during his Last Stand. After Ned’s capture, Dr Nicholson of Benalla removed the sash while treating his wounds and kept it as a souvenir. Dr Nicholson’s daughter donated the sash in 1973. Today it is on display, still stained with Ned’s blood.

The heroic deed, and the Sheltons, remained firmly in Ned’s memory throughout the remainder of his life. In 1880, Ned proudly wore the sash as a cummerbund under his famous suit of armour in the shootout with police at Glenrowan. While Ned was captured after receiving twenty-eight bullet wounds and executed less than five months later on November 11, 1880, the frayed, blood-stained sash still survives today, and is on display at the Costume and Pioneer Museum in Benalla.

Ned was able to rescue the seven year old Richard Shelton from drowning when he fell in the creek opposite the Kelly home. His courage must have been exemplary for the Shelton family saw fit to make a public occasion of it by presenting him with a gold-fringed sash.

Max Brown Australian Son

Working in the Bush

It was inevitable that Ned, the eldest of the Kelly boys, should become a resourceful bush-worker while still in his teens. He did many things to earn a few shillings for the family, such as ring-barking, breaking in horses, mustering cattle, fencing and perhaps a little cattle-duffing on the side. Many of the settlers in the area were small selectors who were at constant war with the big landowners (the squatters) who, at any time, could call on the forces of law and order to protect their interests. In this social war can be found the key to Ned Kelly’s rebellion against authority. The Kelly boys, the Quinns, the Lloyds and the rest used horses like currency.

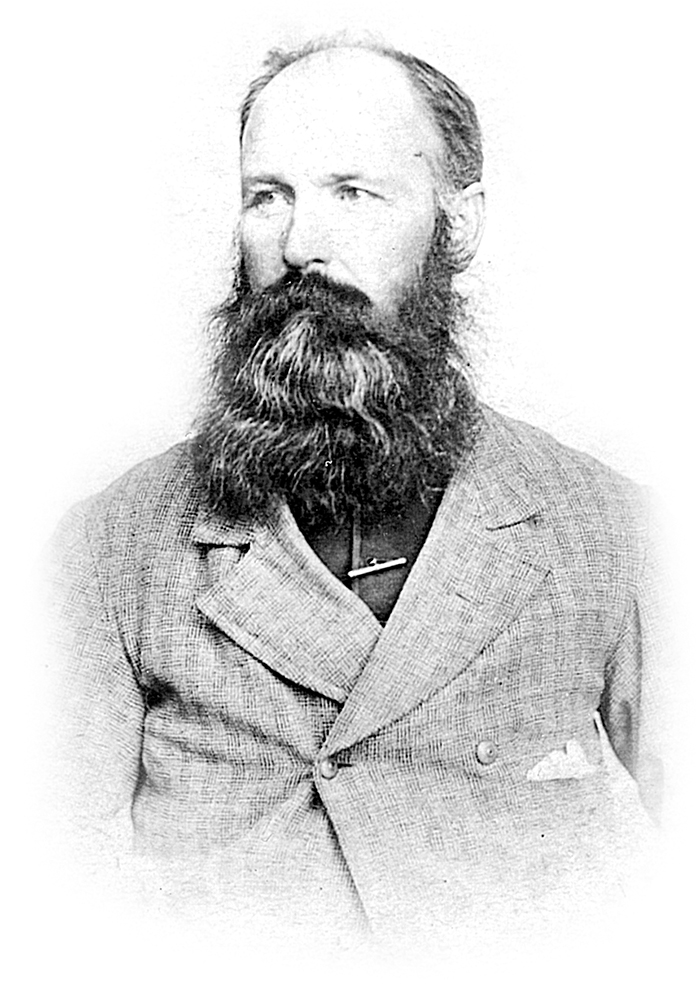

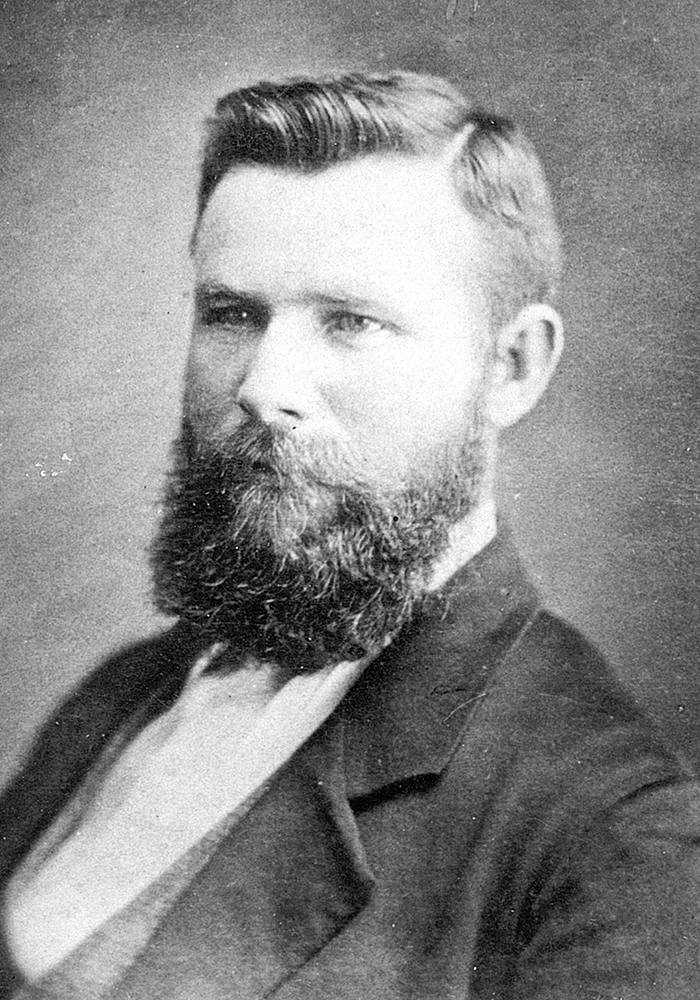

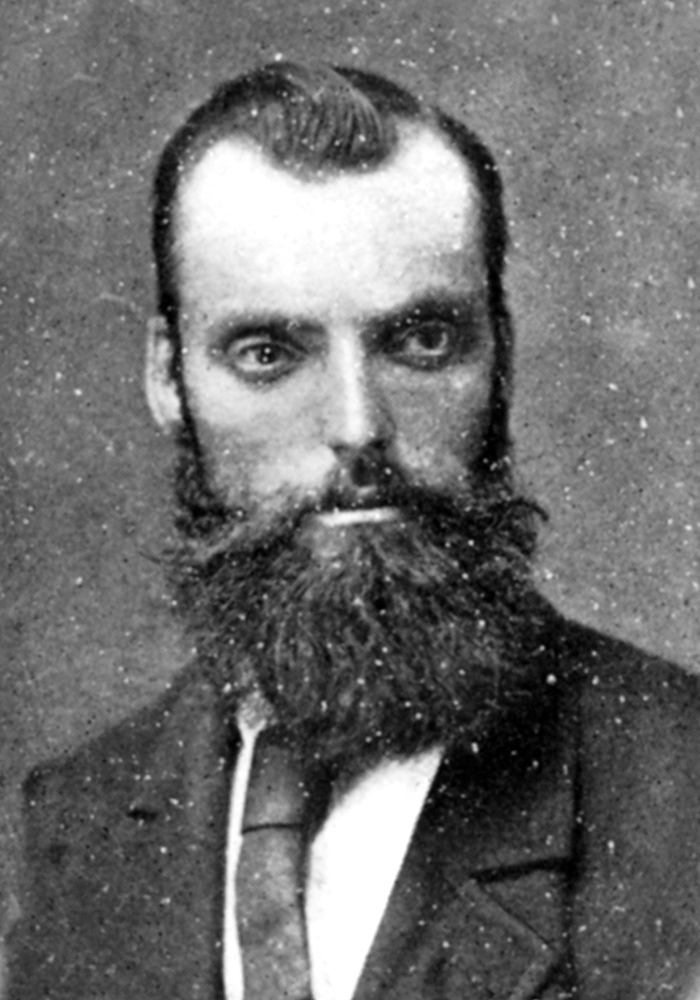

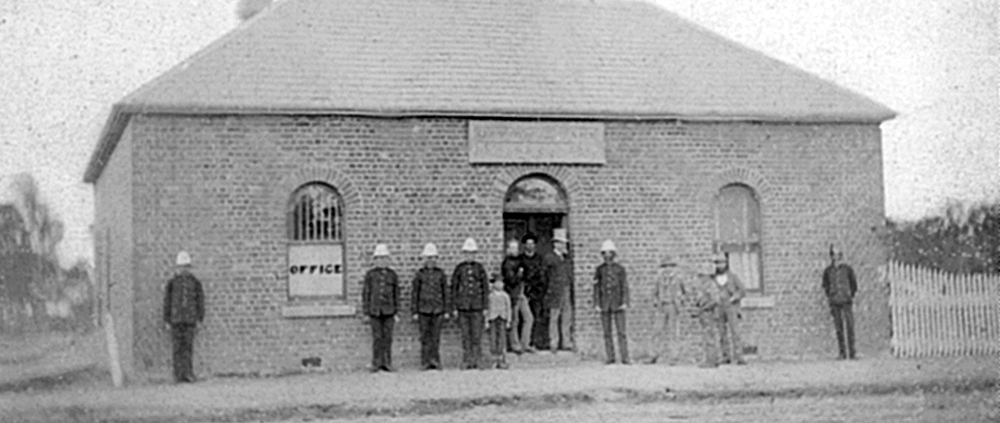

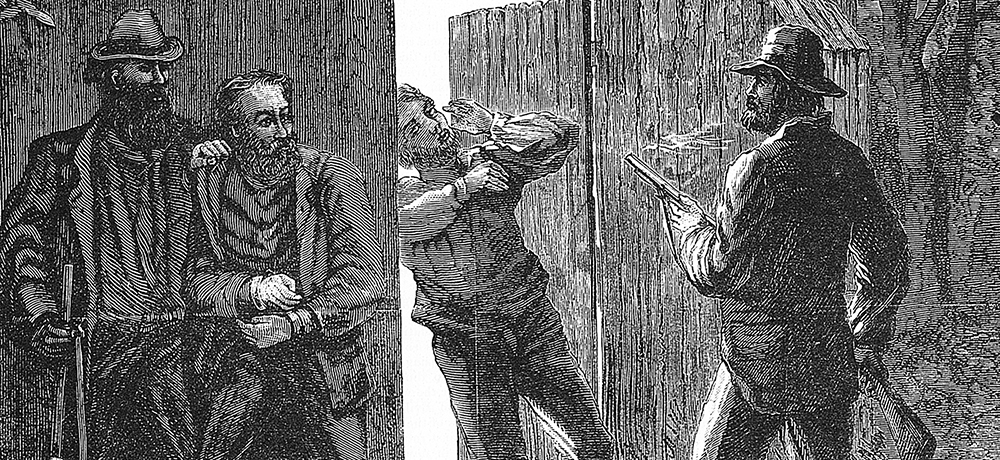

Superintendent Nicolson, officer-in-charge of the Kelly pursuit, ran himself to a standstill after the Euroa robbery and had to be replaced.

Superintendent Nicolson, officer-in-charge of the Kelly pursuit, ran himself to a standstill after the Euroa robbery and had to be replaced.

They regarded all unbranded strays as fair game and the police patrols as their natural enemies. The police in Kelly Country also bitterly resented the clannishness of the small selectors and were determined to break them. When Superintendent Nicholson, a Scot, took over the north-eastern police district, he was told that Mrs Kelly’s house was a notorious meeting place for rogues and cattle-thieves. He gave Mrs Kelly a stern warning, to which she responded with a spirited retort. In his official report, Superintendent Nicholson stated firmly, if injudiciously: ‘The Kelly gang must be rooted out of the neighbourhood and sent to Pentridge gaol, even on a paltry sentence. This would be a good way of taking the flashness out of them’.

The forces of law had already been at work on the ‘Kelly Gang’ as Nicholson chose to call the family. At the age of fourteen, in 1869, Ned was arrested for assaulting a Chinaman. He was kept in the Benalla lockup for ten days and then reluctantly released when the magistrate, Alfred Wyatt, dismissed the charge. A year later Ned was taken on a more serious charge, that of being an accomplice of the bushranger Harry Power. Again, the case against him was dismissed for lack of evidence.

Power was born Henry Johnson in Waterford, Ireland in 1819. He was sentenced to seven years transportation for stealing a pair of shoes in 1840. In 1855, he received a thirteen year sentence for horse stealing and shooting a police trooper. During his stint, Power served time in various prisons including some time aboard the prison hulk ‘Success’ anchored off Williamstown in Hobson’s Bay.

Released in 1862 and now under the name of Harry Power, he was posted ‘illegally at large’ after ignoring his conditions of release. Subsequently, a reward was placed on his head. Harry moved to the North East of Victoria where, in 1864, he was arrested for horse stealing and sentenced at Beechworth Courthouse to seven years imprisonment at Pentridge Prison in Coburg. In 1869, only a few months before he was to be released, Power escaped by hiding in a hole in a new section of prison wall. He then returned to North East Victoria where he was responsible for a spate of armed robberies of travellers, coaches and horses. His territory ranged from Kyneton to Bairnsdale, across the Divide and deep into Gippsland and up to southern NSW. He once held up the Mansfield-Jamieson coach twice in one week.

One night in June, a party of troopers led by Sergeant Montford who had previously arrested Lloyd, and accompanied by the two rival officers – Nicolson spare and prim and Hare huge and popular – set out to make the assault on Power’s hideout above the King valley. Power slept secure in the knowledge that the track to his nest passed within metres of the Quinn homestead where a peacock served as watchdog. Unfortunately, a deluge of rain enabled the intruders to get past the bird without an alarm, with the result when dawn arrived that Nicolson and Hare were able to seize Power and drag him from his shelter. Power was particularly ashamed that he had been caught asleep. “That bloody bird. Well, well, they’ve caught old Harry at last,” he remarked. Whereupon he boiled the billy and cracked jokes. Hare was so big, said Power, that his horse would back away in fright.

Max Brown Australian Son

While roaming the Greta district, Power became friends with the Kellys, Lloyds and Quinns and often stayed with the families. It was here that Harry Power became known as the ‘Gentleman Bushranger’. Many of Power’s victims reported seeing a ‘young man’ in the background during the bail-ups. This young man was to learn a great deal about bushmanship during his brief liaison with the gruff old bushranger. The young man was Ned Kelly, and the lessons learnt would stay with him during his short life. Harry Power was made famous by being credited with tutoring a young Ned Kelly in the ways of bushranging during 1870. It was a brief affair, one where Ned made only five pounds and which nearly cost him his life. Ned was arrested as Harry’s accomplice in May 1870, however, the charge was later dismissed.

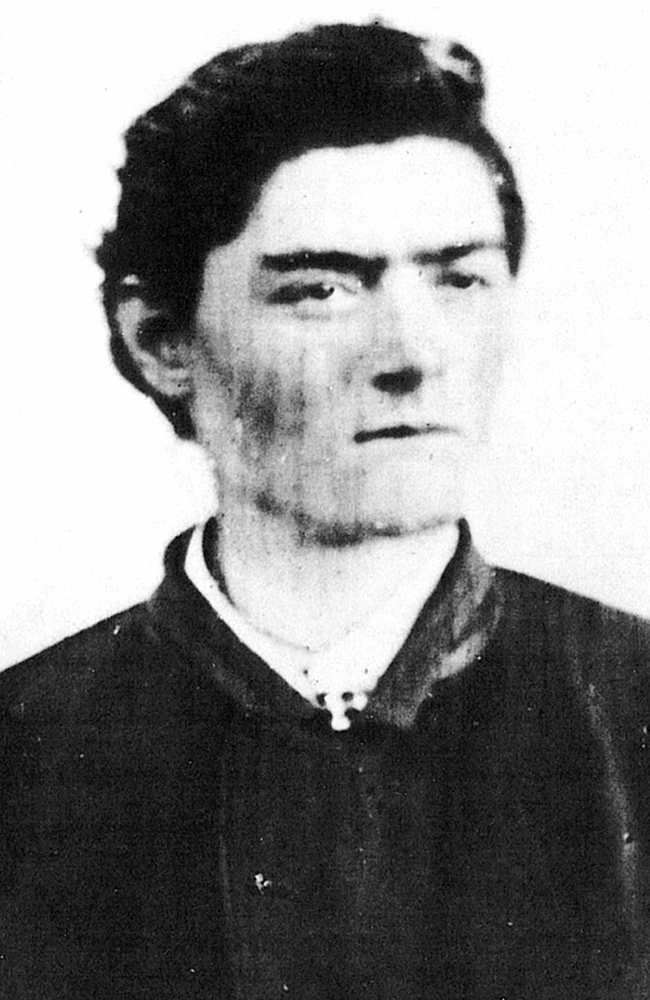

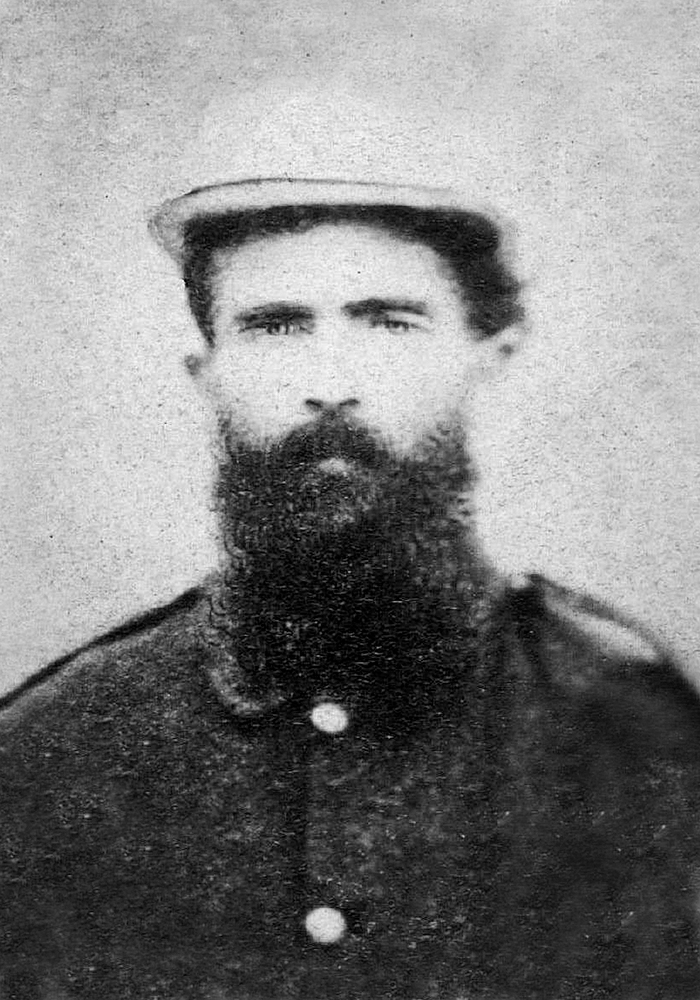

Ned Kelly at 15, charged with helping Harry Power in two robberies, sits for an unknown photographer at Kyneton, where he was held on remand. He was treated well by Sergeant Babington and, after being released, wrote to Babington when he needed help.

Ned Kelly at 15, charged with helping Harry Power in two robberies, sits for an unknown photographer at Kyneton, where he was held on remand. He was treated well by Sergeant Babington and, after being released, wrote to Babington when he needed help.

Initially, Ned Kelly was blamed for Power’s capture but it was later revealed his uncle, Jack Lloyd, a long time friend of Harry’s, had led police to the bushrangers camp and pocketed five hundred pounds for his trouble. On the charge of three armed robberies (although he probably committed more than ninety offences while at large) Power was sentenced to fifteen years imprisonment with hard labour to be served at Pentridge. He survived his prison term, being released in 1885, an old and sick man.

For a period afterwards he acted as a tour guide aboard the hulk ‘Success’ under the title ‘The last of the Bushrangers’. In 1891, Power made his last trip to the North East where it was reported he slipped and drowned whilst fishing in the Murray River near Swan Hill. He survived his famous apprentice by eleven years. Mrs Kelly may have been half right when she called him a ‘brown paper bushranger’ but his death signified the end to the ‘Golden Days of Bushranging’ for Victoria’s North East.

A Wild Time

The police did not relax their interest in Ned. He was jailed for six months for assaulting a hawker and in the following year, 1871, came disaster. He was sentenced to three years in Pentridge gaol for receiving a ‘borrowed’ mare. The borrower was his friend Isiah ‘Wild’ Wright, who bewilderingly received a sentence of only eighteen months. ‘Wild’ Wright, was a flamboyant young Mansfield identity who had lost a horse while at the Kelly homestead and failed to inform Ned Kelly that it was stolen. Ned found the horse and rode it past the Greta Police Station which earned him a brutal pistol-whipping from a local trooper Senior Constable Hall, who had initially tried to shoot him. Hall’s frank admission of beating Kelly over the head at the preliminary hearing did not encourage the police to persist with an assault charge, but Kelly was refused bail. Quoted from the Jerilderie Letter, Ned recounts his severe bashing at the hands of the Greta Police.

I dare not strike any of them as I was bound to keep the peace or I could have spread those curs like dung in a paddock. They got ropes, tied my hands and feet and Hall beat me over the head with his six chambered colts revolver. Nine stitches were put in some of the cuts by Dr Hastings. And, when Wild Wright and my mother came they could trace us across the street by the blood in the dust and which spoiled the lustre of the paint on the gate-post of the Barracks Hall.

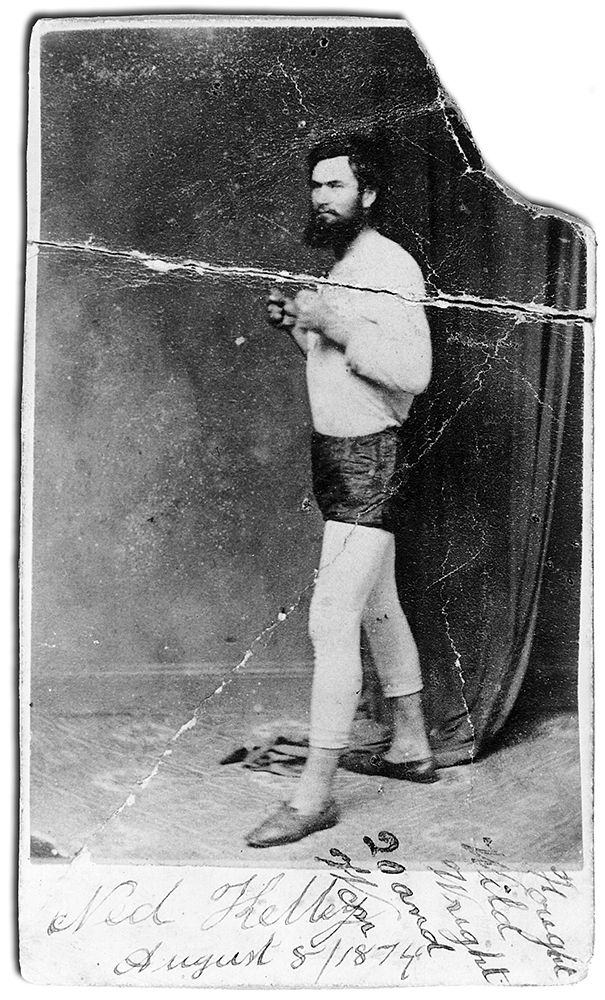

Next, Isaiah Wright was arrested, then – as Kelly had been in gaol when the mare disappeared – the theft charge was changed to one of receiving. Ned was sentenced to three years hard labour, however, Wild Wright who actually stole the horse, received only eighteen months! Upon his release, Ned challenged Wild to a bare-knuckle fight which lasted twenty rounds before Kelly was declared the winner at Beechworth on August 8, 1874.

Ned had also discovered that his mother had married again and her new husband, George King, was from California. He was later described by Ned as a clever horse-thief. King gave Mrs Kelly (she retained her first husband’s name) four children and then moved on, never to be heard from again. Ned had worked with George through most of 1877, running stolen horses across the Murray River for sale in New South Wales. This major horse stealing racket performed a significant raid on the district’s most powerful squatter, James Whitty.

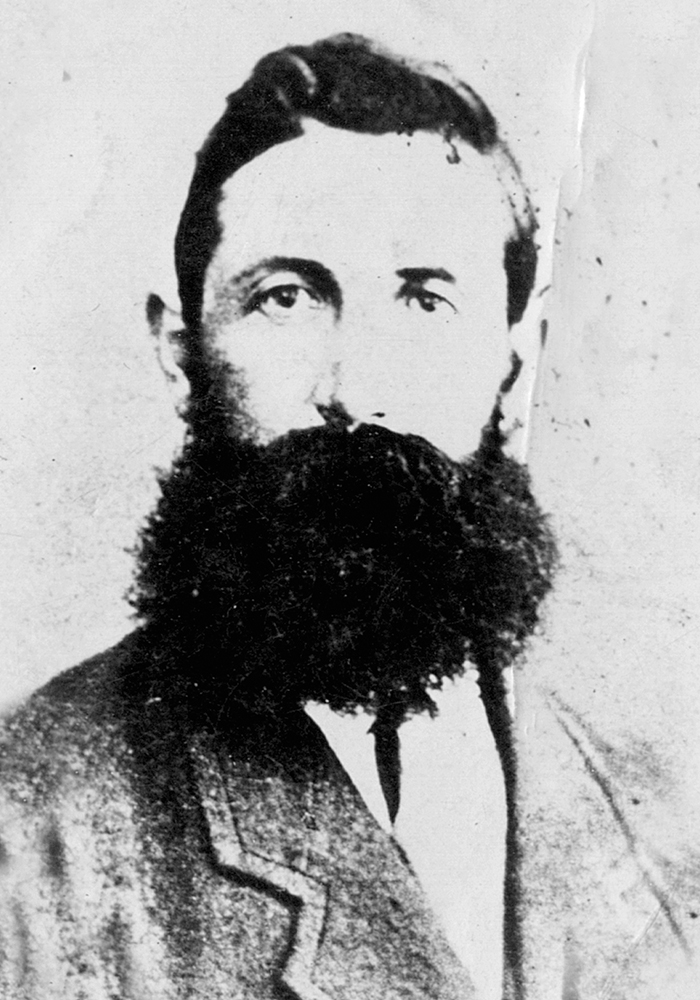

Ned at nineteen, a study by Melbourne photographer Chidley. It celebrates Ned’s victory over Wild Wright in a twenty-round bare-knuckle match. Image: Max Brown

Ned at nineteen, a study by Melbourne photographer Chidley. It celebrates Ned’s victory over Wild Wright in a twenty-round bare-knuckle match. Image: Max Brown

In 1877, Ned Kelly was arrested for ‘Riding across a Footpath and Drunkenness’ which was a curious charge as Ned was known to hardly drink. Many suspected the police of spiking his liquor as Fitzpatrick was seen at the bar with him on the night in question. Ned took umbrage at the police attempt to handcuff him and an epic fight ensued between Kelly and his four escorts Sergeant Whelan, Constable Alexander Fitzpatrick – later to be driven out of the police force due to numerous charges of neglect of duty and misconduct – Constable Day, and Constable Lonigan who Ned was to later shoot dead at Stringbybark Creek.

Ned took refuge in the boot maker’s shop, across the road from the Benalla Courthouse, after escaping a brutal police bashing on his way to court. During the fracas, Lonigan grabbed Ned by his ‘privates’ and squeezed so hard it was to cause Kelly problems for the rest of his short life. Ned was said to have howled in pain, ‘Well Lonigan, I never shot a man yet but if I do so help me God you will be the first’ – which ironically a year later he did. Eventually, Ned was subdued by a sympathetic Magistrate, William Maginness, who led him to the Courthouse.

The Fitzpatrick Mystery

When Ned’s sixteen year-old brother, Dan, became a suspect, a disreputable young police constable named Alexander Fitzpatrick tried to arrest the boy at the Kelly homestead. A mysterious brawl erupted. A drunken Fitzpatrick swore that Mrs Kelly had assaulted him and that Ned Kelly had shot him in the wrist. Ned and Dan became fugitives. Mrs Kelly, with a baby at her breast, was sentenced to three years hard labour. Her son-in-law, Bill Skilling (Skillion) and a neighbour, Bill ‘Bricky’ Williamson, each received six years hard labour. Ned and Dan offered to surrender if their mother was released. The offer was refused.

Brother Dan Kelly had fallen foul of the law while still in his teens. He was given three months for damaging property, but later the chief police witness against him was charged with perjury. On his release from prison Dan went home unaware that the police, unable to find the horse-thief, King, had sworn warrants against both Ned and Dan. It was reported that Ned had slipped over the border into New South Wales, however, evidence suggests he was very close by on the night of the ‘Fitzpatrick Incident’. An incident that should never have occurred if proper police guidelines had been observed, in particular the command that police must not act alone when executing an arrest warrant.

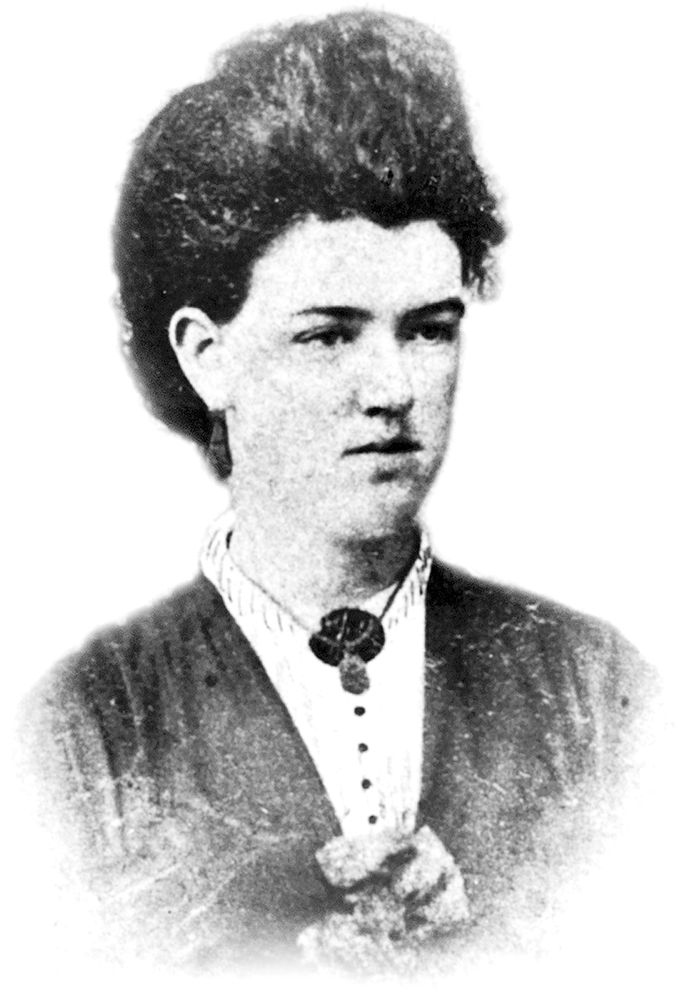

Kate Kelly was a quiet 14-year-old when she became caught up in the Fitzpatrick incident. A popular heroine of the Kelly story, she actually played a less important role than her older sister, Maggie. Image: Max Brown

Kate Kelly was a quiet 14-year-old when she became caught up in the Fitzpatrick incident. A popular heroine of the Kelly story, she actually played a less important role than her older sister, Maggie. Image: Max Brown

The trooper who came with the warrant was a weak willed man named Alexander Fitzpatrick, who had called at a tavern on his way to Mrs Kelly’s place to fortify his intent. It is quite possible Fitzpatrick was looking to make himself some sort of hero by travelling solo. The trooper found Dan at home with Mrs Kelly and the girls, as well as Will Skillion, Maggie Kelly’s husband, and a neighbouring selector named Williamson. Not long after the lone trooper entered the homestead, violence erupted. Fitzpatrick made a drunken pass at Kate Kelly. Dan knocked him down and, in the ensuing scuffle, the trooper’s gun went off and he cut his wrist, most likely on the door-latch. Mrs Kelly was full of concern. She bandaged his wrist and he was invited to have supper with the family and ‘let bygones be bygones’. On his way back to police barracks, Fitzpatrick had some more brandy. He then reported to his superiors that Dan Kelly had resisted arrest, and that Ned had burst into the room and shot him in the wrist. Ned then offered to cut out the bullet with a rusty razor blade but Fitzpatrick declined, opting to use his penknife to dig it out.

I hear previous to this Fitzpatrick had some conversation with Williamson on the hill. He asked Dan to come to Greta with him as he had a warrant for him for stealing Whitty’s horses. Dan said all right. They both went inside. Dan was having something to eat. His mother asked Fitzpatrick what he wanted Dan for. The trooper said he had a warrant for him. Dan then asked him to produce it. He said it was only a telegram sent from Chiltern, but Sergeant Whelan ordered him to relieve Steel at Greta and call and arrest Dan and take him into Wangaratta next morning and get him remanded. Dan’s mother said Dan need not go without a warrant unless he liked and that the trooper had no business on her premises without some Authority besides his own word. The trooper pulled out his revolver and said he would blow her brains out if she interfered in the arrest. She told him it was a good job for him Ned was not there or he would ram the revolver down his throat. Dan looked out and said Ned is coming now. The trooper, being off his guard, looked out and when Dan got his attention drawn, he dropped the knife and fork which showed he had no murderous intent and slapped Heenan’s hug on him, took his revolver, and kept him there until Skillion and Ryan came with horses which Dan sold that night. The trooper left and invented some scheme to say that he got shot, which any man can see is false. He told Dan to clear out, that Sergeant Steel and Detective Brown and Strachan would be there before morning.

Ned Kelly’s Jerilderie Letter

A doctor giving Crown evidence readily accepted the contribution of Fitzpatrick’s penknife to the injury, while apparently reluctant to state definitely that a bullet had been involved. Ned Kelly may have had a revolver at the time of the incident, but it seems highly unlikely that it produced the constable’s wound, certainly not as alleged by Fitzpatrick. Even the acting commissioner of police later admitted Fitzpatrick was ‘a liar’. In all likelihood both Ned and Joe were present at the Kelly homestead on the night Fitzpatrick came calling. By the time a troop of police had surrounded the Kelly homestead, the boys had gone bush.

In spite of Mrs Kelly’s protests that Ned was four hundred miles away and, anyway, nobody had shot Fitzpatrick, arrests were made. For assisting in the attempted murder of a police officer, Judge Redmond Barry sentenced Skillion and Williamson to six years each, and Mrs Kelly herself was sentenced to three years in gaol. Barry at the time also remarked that, ‘had Ned been present I would have sentenced him to twenty one years’. Later, Fitzpatrick was to be discharged ignominiously from the police force for misconduct in another case. But by then the damage had been done.

The police have treated my children very badly. I have three very young ones, and had one only a fortnight old when I got into trouble (referring to her recent imprisonment in connexion with the assault on Constable Fitzpatrick at Greta). That child I took to Melbourne with me; but I left Kate and Grace and the younger children behind. The police used to treat them very ill. They used to take them out of bed at night, and make them walk before them. The police made the children go first when examining a house, so as to prevent the outlaws, if in the house, from suddenly shooting them. Kate is now only about 16 years old, and is still a mere child. She is older than Grace. Mrs. Skillion is married, and, of course, knew more than the others, who are mere children. She is not in the house now. Mr. Brook Smith was the worst behaved of the force, and had less sense than any of them. He used to throw things out of the house, and he came in once to the lock-up staggering drunk. I did not like his conduct. That was at Benalla. I wonder why they allowed a man to behave as he did to an unfortunate woman. He wanted me to say things that were not true. My holding comprises 88 acres, but it is not all fenced in. The Crown will not give me a title. If they did I could sell at once and leave this locality. I was entitled to a lease a long time ago, but they are keeping it back. Perhaps, if I had a lease, I might stay for a while, if they would let me alone. I want to live quietly. The police keep coming backwards and forwards, and saying there are ‘reports, reports.’ As to the papers, there was nothing but lies in them from the beginning. I would sooner be closer to a school, on account of my children. If I had anything forward I would soon go away from here.

Mrs Ellen Kelly from the May 14, 1881 visit by the 1881 Royal Commission On The Police Force In Victoria.

Ned Kelly swore vengeance. Restrained by his friends, he instead wrote an impassioned letter to Magistrate Wyatt, offering to surrender his own person ‘to any charge’ in exchange for his mother, but Wyatt was powerless to act. By then the police were increasing their efforts to get Ned Kelly, so he and Dan vanished overnight from the district. The government offered a reward of one hundred pounds each for their apprehension. Ned and Dan went into hiding in the Wombat Ranges, some twenty miles from Mansfield in rough country. They cleared the ground and built a slab hut near the banks of a creek, and spent their time panning for alluvial gold.

Here they were joined by two old friends Steve Hart, a part time jockey from Wangaratta, and Joe Byrne, son of a gold prospector at Beechworth. Both had previously served short prison sentences. Joe was a Woolshed lad, born around 1857 of Irish-Catholic extraction. His father died when Joe was around twelve years old, after a working life as a digger then a dairyman. Byrne went to school with Aaron Sherritt and they later served six months together for the unlawful possession of meat. Later Joe was fined for the illegal use of a horse. Like the rest of the Kelly Gang, Byrne was a good shot and fine horseman. He practiced riding down steep gullies for fun. He was also an experienced alluvial miner and could speak fluent Cantonese having grown up amongst the Chinese diggers, which came in handy during his numerous visits to their opium dens. Joe Byrne was part of the Kelly Gang because he happened to be around on the day of the Stringybark killings. On another day the gang could have been made up from an entirely different cast including Tom Lloyd, Ned’s cousin, or Wild Wright, Ned’s mischievous Mansfield mate, or even Aaron Sherritt.

Joe Byrne, however, was no ring-in. He became mates with Ned Kelly in 1876 and trusted him completely. He is remembered as Ned Kelly’s lieutenant. The man Ned consulted on strategy. Ned saw Joe as a wise, patient sort of fellow unlike Dan or Steve which is why he tolerated Byrne’s relationship with Sherritt, even when others were branding Aaron as a police informer. At Stringybark Creek the evidence suggests that Joe shot dead Constable Scanlon after Ned had blown him off his horse. Scanlon’s ring was worn by Joe Byrne at Glenrowan. Aaron Sherritt inadvertently implicated Joe as a Kelly Gang member when, on being asked to become an police informer said he would consider the deal if Byrne’s life was spared. Joe’s high-heeled boots were his trademark, being referred to as larrikin heels in late nineteenth century Victoria. Byrne was seen as one of the most glamorous gang members with his handsome colonial boy charm and his strong opposition to police law and order. Joe enjoyed reading a fine book and was a highly proficient writer. It was Joe who penned Ned’s words in the famous Jerilderie letter as well as the red inked Euroa letter, sent to Victorian MP Donald Cameron and Superintendent Sadleir. It is also understood Joe composed a number of ballads extolling the virtues of the Gang’s escapades. A verse from one of Joe’s songs goes:

My name is Ned Kelly,

I’m known adversely well.

My ranks are free,

my name is law,

Wherever I do dwell.

My friends are all united,

my mates are lying near.

We sleep beneath shady trees,

No danger do we fear.

Ned Kelly was a natural leader, but it was later revealed that he had no plan to carry out organised crimes from his hideout. With the help of various friends, the Kelly boys operated a gold mine and a whiskey still on Bullock Creek in an attempt to raise enough money to mount a retrial for their mother.

Stringybark Shootout

The police hunt intensified. In late October 1878, two police parties set out for the Wombat Ranges from Greta in the north and Mansfield in the south, attempting to take the Kelly brothers in a pincer movement. This trap would then close and result in the triumphant return of the police with the bodies of Ned and Dan Kelly. One of the police parties was led by Sergeant Kennedy, with Constables Lonigan, Scanlon and McIntyre, who rode out from Mansfield. They wore no uniforms but all were heavily armed, for when the Gang rode out of Stringybark Creek they took with them four Webly revolvers, Scanlon’s .500 calibre seven shot Spencer Carbine (borrowed from the Woods Point gold escort), and Kennedy’s double-barrelled shot gun (borrowed from Reverend Sanderford, the Mansfield Vicar).

Constable Thomas Lonigan was included in the Stringybark party because he could identify the Kellys. In September 1877, Ned was arrested in Benalla for riding on a footpath drunk and conducted across the Broken River to the barracks where he claimed his liquor had been spiked. In charge was Sergeant Whelan who remembered him from the ‘Ah Fook’ matter of eight years before. Whelan took three troopers along next morning to escort him to court – Constables O’Dea, Lonigan and Fitzpatrick, the last named a raw recruit from Richmond Depot who impressed Ned as ‘rather genteel, more fit to be a starcher to a laundress’. The party was crossing the street to the courthouse, when – in accordance with the practice of making the new chum do the dirty work – Fitzpatrick set out to handcuff the prisoner.

Whatever was said is not known, but Kelly brushed the handcuffs aside and ran back into a boot maker’s shop. Before he knew it, Fitzpatrick had him by the throat and Lonigan by the testicles. He hit out, and the troopers were preparing for a third sally when Mr McInnes, J.P., the local flour miller, intervened, took the handcuffs and said, “Come on, Ned, this is the only way out.” As usual, Ned responded to a friendly approach and the miller locked the handcuffs on him, but the legend has it that he turned as he left the shop and remarked, ‘Well, Lonigan, I never shot a man yet; but if I do, so help me God, you’ll be the first!’

On the 25th they made camp at Stringybark Creek, unaware that only a mile away was the Kelly’s camp. Making one of his regular reconnoitres, Ned spotted the police camp and hurried back to raise the alarm believing, quite rightly, that he and Dan would be shot on sight. There had been recent, well-publicised cases of trigger-happy New South Wales police killing suspects and there is persuasive evidence that the Victoria police searching for the boys were equally likely to shoot first. One police officer was quoted as saying ‘If I come across Ned Kelly I’ll shoot him like a dog’.

Not only were the police well armed, they had also bought along a pack horse fitted with heavy leather straps, made especially for the expedition. The sole purpose of these straps was to lash tightly the bodies of Ned and Dan for their return to Mansfield.

Sergeant Michael Kennedy took good care in organising the party. His first choice was an old comrade, Mounted Constable Michael Scanlon, a former prospector and crack shot who knew the Mansfield country. Scanlon was temporarily relieved at Mooroopna. Constable Lonigan, of Violet Town, the one who had grabbed Ned’s testicles in the boot maker’s shop, was included because he knew the Kellys. Constable McIntyre, an Orangeman who had a reputation as a camp cook, made the fourth member of the party. Disguised as prospectors, the four troopers set out with considerable secrecy from Mansfield on Friday morning, October 25, 1878. Kennedy and Scanlon evidently decided to split the reward, for they said nothing of any plan, but instead vacated camp at six the next morning, leaving Lonigan and McIntyre to keep watch and prevent their mounts from straying. The two troopers were relaxing by the campfire when Ned, Joe, Steve and Dan emerged silently from the bush. Intending to disarm the police and take their horses, they challenged the troopers and ordered them to surrender.

I was compelled to shoot them, or lie down and let them shoot me it would not be wilful murder if they packed our remains in, shattered into a mass of gore to Mansfield, they would have got great praise and credit as well as promotion but I am reconed a horrid brute because I had not been cowardly enough to lie down for them under such trying insults to my people certainly their wives and children are to be pitied but they must remember those men came into the bush with the intention of scattering pieces of me and my brother all over the bush…

Lonigan jumped to his feet and drew his revolver but Ned shot him dead. McIntyre surrendered immediately. When Kennedy and Scanlon returned to the camp Ned called to them to ‘bail up’. Instead the troopers opened fire. A gunfight followed, with the policemen dodging from tree to tree. Ned, whose shooting was deadly even in the fading light, killed Kennedy while Joe Byrne finished off Scanlon but McIntyre managed to escape on Kennedy’s horse. The gang then covered the bodies of the police troopers with blankets, took their weapons and rode out.

Kennedy kept firing from behind the tree my brother Dan advanced and Kennedy ran. I followed him he stopped behind another tree and fired again. I shot him in the armpit and he dropped his revolver and ran I fired again with the gun as he slewed around to surrender. I did not know that he had dropped his revolver, the bullet passed through the right side of his chest and he could not live or I would have let him go…

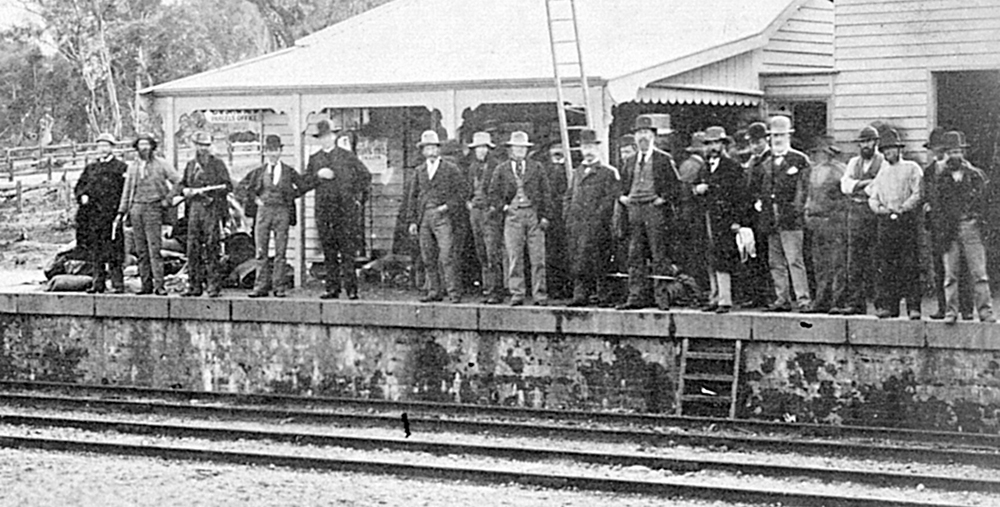

Constable McIntyre reached Mansfield to raise the alarm and told a story of a cowardly ambush by the Kelly’s and a mass slaughter, which shocked Mansfield and, in time, the whole country. Ned Kelly, Dan Kelly, Steve Hart and Joe Byrne were proclaimed outlaws, to be taken dead or alive. Two hundred police were drafted into the area and skilled native troopers were brought in from Queensland.

The police manhunt drew a blank. Even with emergency powers to enter premises, search and arrest without warrant, the police could find no trace of the Kelly Gang. Suspected sympathisers were arrested and held for weeks on remand. Public sympathy for the police vanished and resentment set in, even among law-abiding citizens who deplored the shooting of Kennedy and his men.

Then at last the police got help from a friend of Joe Byrne named Aaron Sherritt, who turned informer. Although in reality it is more likely Sherritt was trying to line his pockets with some easy money. While he may also have attempted to throw the scent off the real trail, Sherritt eventually made the fatal mistake of not letting Joe Byrne and the rest of the Kelly Gang in on his plan. However, at this stage Ned’s main concern was a lack of money. Ned decided that funds must be raised to keep them going and to help sympathisers who needed bail money and pay off farming debts. It was decided the Gang needed to rob a bank and the town of Euroa held the perfect prize.

Taking the Banks

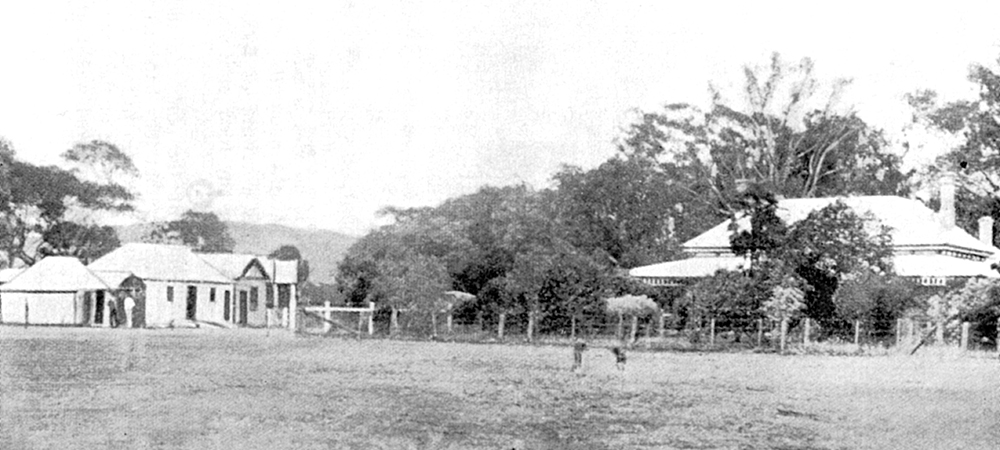

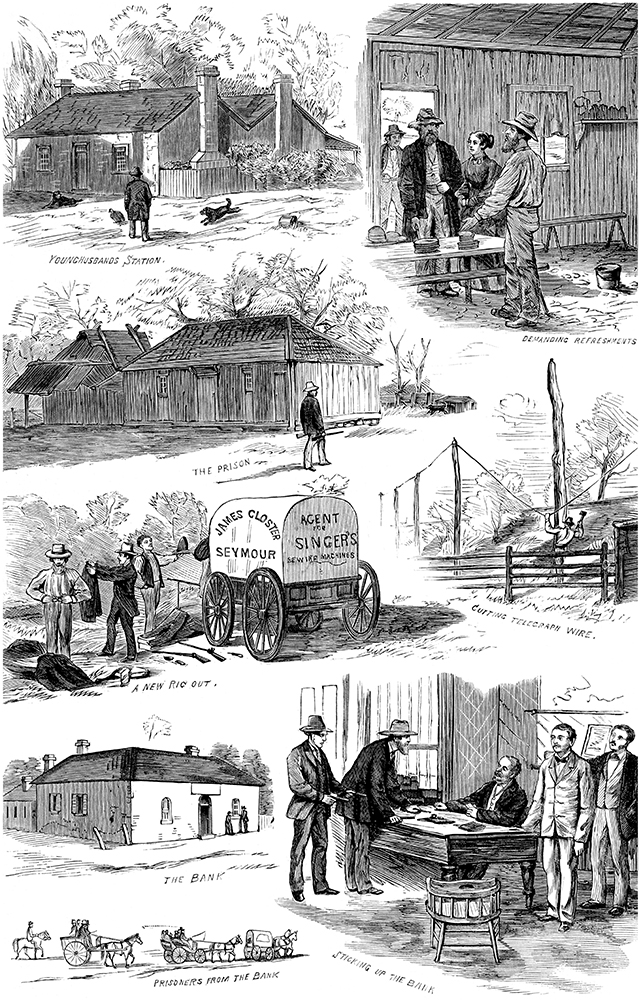

On December 10, 1878, the Kelly Gang invaded a station property at Faithfull’s Creek, twenty-seven miles west of Benalla. Twenty-two people at the sheep-station were rounded up and locked in a storeroom while the Kelly’s’ horses rested. Then, leaving Joe Byrne to guard the prisoners, Ned, Dan and Steve drove into Euroa in a commandeered hawker’s cart. Euroa then had a population of no more than three hundred, with an unpretentious brick building on the main street which was being rented from the local blacksmith by the National Bank. At 4pm Ned Kelly entered the bank with a drawn gun, and Dan came in from the rear. Ten minutes later they were out on the street again, richer by £2,260 in notes and gold from the Bank’s safe after cutting the telegraph lines from Melbourne to Benalla to prevent anyone alerting the authorities.

Euroa boasted an old town, and near the railway station, a new town comprising bank, hotel, general store, school and public hall, with most of the business activity around the hall. Steve reported, amongst other matters, that Tuesday would suit the robbery, the sole constable would be at the Licensing Court and the stationmaster deposited takings at the National Bank after the 3.30pm goods train. The street door was left ajar until 4pm. The bank was very hot with the sun blazing squarely on the front. The outlaws, meanwhile, raked together an extra sixty pounds plus 30 ounces of gold, 80 rounds of ammunition and a number of deeds and mortgages that they placed in a bag. When they returned to the parlour they asked for a drink, and Scott offered them whisky, which they drank only after he had sampled it.

Max Brown Australian Son

By the time Nicolson reached Younghusbands’ Station the morning was one of heat which shimmered in the air against a cloudless sky. He was already exhausted. The troopers had been circling the homestead since daylight trying to pick up tracks. The earth bore evidence of horses cutting, turning and crisscrossing in every direction. In fact farmers and others who looked to the Kellys as their champions had converged on the area and wiped out every chance of following them.

Max Brown Australian Son

An artilleryman, who was stationed in the town soon afterwards, reported, ‘The people in the bank told me that with the exception of the robbers taking the money, they never offered the slightest insult to anyone. I also visited the Younghusbands station where Joe Byrne was sentry over thirty persons while the others were in the bank, and was told everywhere that the outlaws were undoubtedly police-made criminals’. The Government of Victoria then increased the rewards on the heads of the Kelly Gang to £1000 each, and military guards were posted on all banks in the north-eastern district. Two months later, Ned Kelly and his men crossed the border into New South Wales and struck again.

Funding a Republic

Circumstances had forced Ned’s hand once again. The Gang had been alerted to a number of their supporters being harassed by the local authorities to the point where livelihoods were at stake. Ned needed a large amount of cash to cover the lost earnings and expenses his friends and relatives had to endure when their men folk were locked away without trial for months on end while their fields remained unsown and stock confiscated.

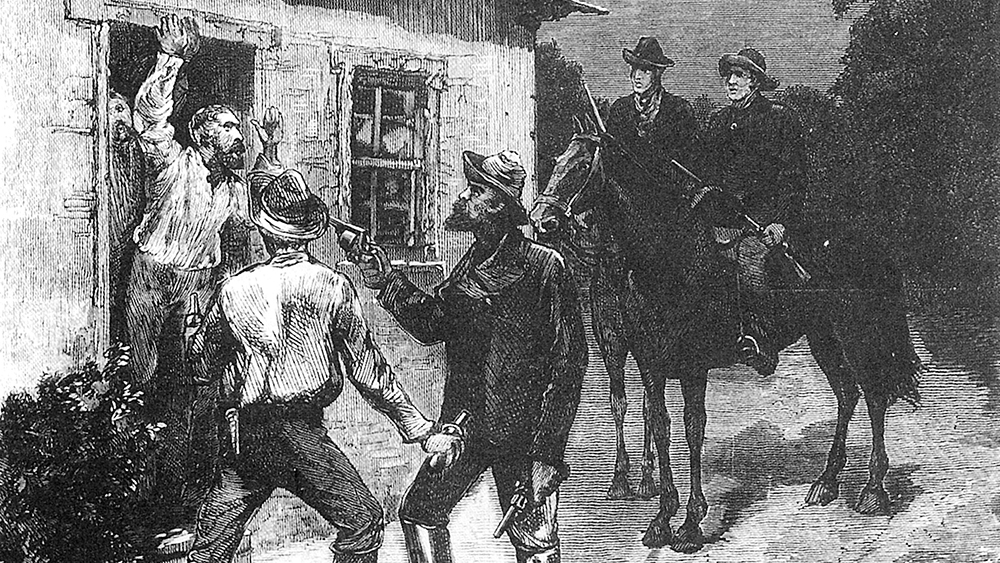

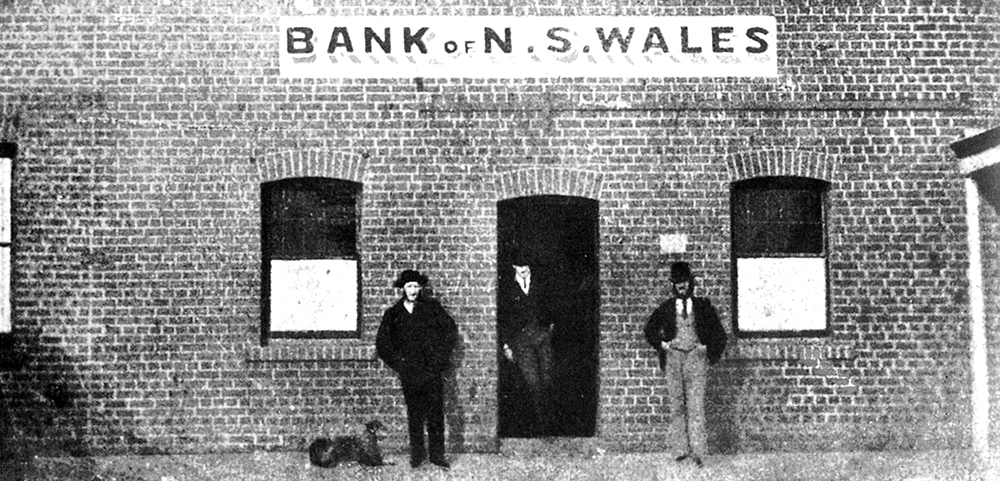

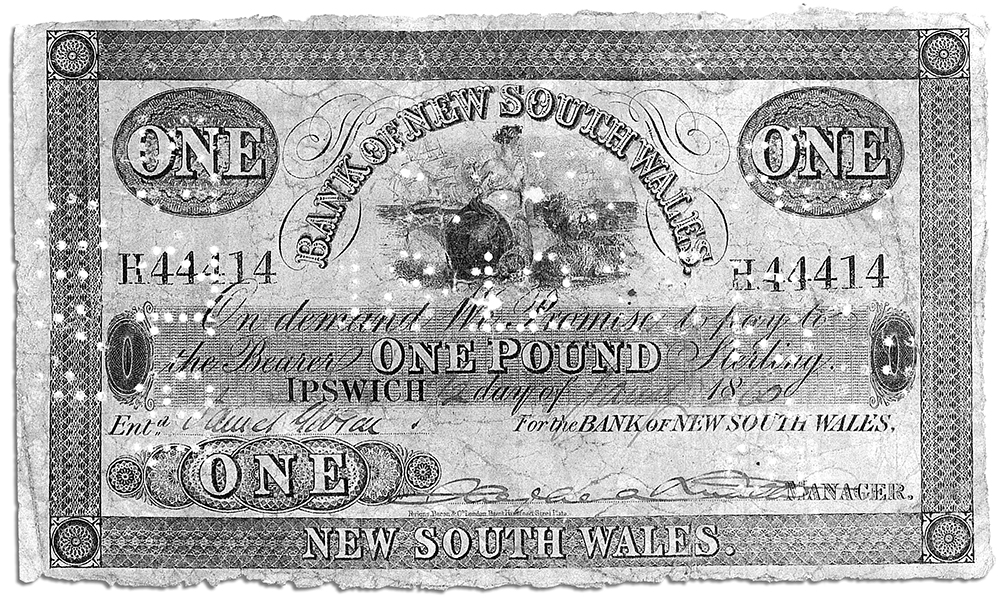

This time their target was the Bank of New South Wales at Jerilderie. It was a Saturday night and they captured the two local policemen and locked them up. Then they dressed themselves in police uniforms and stabled their horses. Next day, Ned supervised the rounding-up of more than sixty townspeople in the dining room of the Royal Mail Hotel, next door to the bank. Then he lectured to the captive audience from a document dictated by Ned to Joe Byrne, which he intended should be read by all the world. It was a remarkable document — autobiography, statement of fact and self-justification — which ran to well over 7500 words — and became known as The Jerilderie Letter.

On Monday morning, Ned went in search of the local newspaper editor to have it printed, but the editor had gone into hiding. Ned had planned to distribute his manifesto after having it printed by the editor Samuel Gill, however, Gill, after hearing about the ‘new’ police in town by a Mrs Devine, became suspicious and ran away. Carefully checking to make sure all the telephone wires out of town had been cut, Ned then proceeded to rob the bank. The Bank of New South Wales lost over £2000 in notes and coin that day. Ned gave his manifesto to one of the tellers, who swore he would give it to Donald Cameron MP, but instead he passed it on to the Crown Law Office in Melbourne.

The statement was then carefully copied then put away and was not produced at Kelly’s trial; nor were its contents made known to the press. It was not until the 1930s that it was even made available to the public. By most accounts, after Jerilderie, the Kelly Gang went into hiding in the Bogong high plains, however, reports circulated that members of the Gang were seen as far away as Melbourne and the Goulburn. The Victorian government increased the Kelly reward to £4000, matched by £4000 from New South Wales — the total worth more than $2 million today. But the Kelly Gang had disappeared and would not be seen for seventeen months until, spurned on by increased police provocation, Ned and the boys were incited to one final act.

Under the spot light

Increasingly frustrated by support for the Gang the Victorian Police Force, under direction from Chief Commissioner Frederick Charles Standish, locked up Kelly friends and relatives for months without trial. When this move backfired, the police drew up a blacklist of Kelly associates, or ‘sympathisers’, who would not be allowed to take up land in the north-east. This ill-advised action tipped the Kelly outbreak into rebellion. Ned and the Gang advanced plans for a Republic of North-Eastern Victoria, to be launched by a pre-emptive strike at their police enemies. But one of those enemies was laying his own devious plan to destroy the Gang.

Aaron Sherritt, a lifelong friend of Joe Byrne, had been a key Kelly agent while pretending to help the police. A detective set out to incriminate Sherritt in the eyes of the Gang. A Detective by the name of Ward put in motion a blood thirsty trap using Sherritt as the bait. By spreading rumours, falsifying reports, and even stealing a saddle, Ward managed to put Sherritt under the spot light. By making Aaron his number one informer, even if his leads were vague at best, both Joe and Ned were alerted to a spy in their midst. If they broke from cover to kill Sherritt, the police would at last have a chance to capture or kill the outlaws. One night Aaron Sherritt opened his door to find Joe Byrne standing there. Without a word, he shot Sherritt dead. Four armed police had been entrusted with the protection of Sherritt and his family who, by then, were on the police payroll.

Joe Byrne and Dan Kelly challenged them to come out and fight but the troopers declined, and instead hid under the Sherritt’s bed. After threatening to burn the house down the two outlaws rode 65 kilometres across country to join Ned and Steve Hart at Glenrowan. The Gang had taken over the town in preparation for the derailment of the Police Special. The four outlaws waited, with their armour, in the Glenrowan Inn ready to advance on the wrecked train and do battle with any survivors. Their plan depended on news of Sherritt’s murder reaching police in Benalla. However, the police party assigned to protecting Aaron did not venture out of Sherritt’s hut until the next afternoon, so the police train did not set out from Melbourne until just after 10pm on Sunday – thirty hours after Aaron Sherritt’s death.

After months of delay, the press announced that twenty native police were en route from Queensland. Publication of the fact was a deliberate attempt to foil his efforts to capture the bushrangers, declared the Acting Chief Secretary, Sir Bryan O’Loghlen. In the event, the twenty trackers proved to be six. They arrived in March after a voyage to Sydney in which all were extremely sick, especially Corporal Sambo who had contracted congestion of the lungs.

Max Brown Australian Son

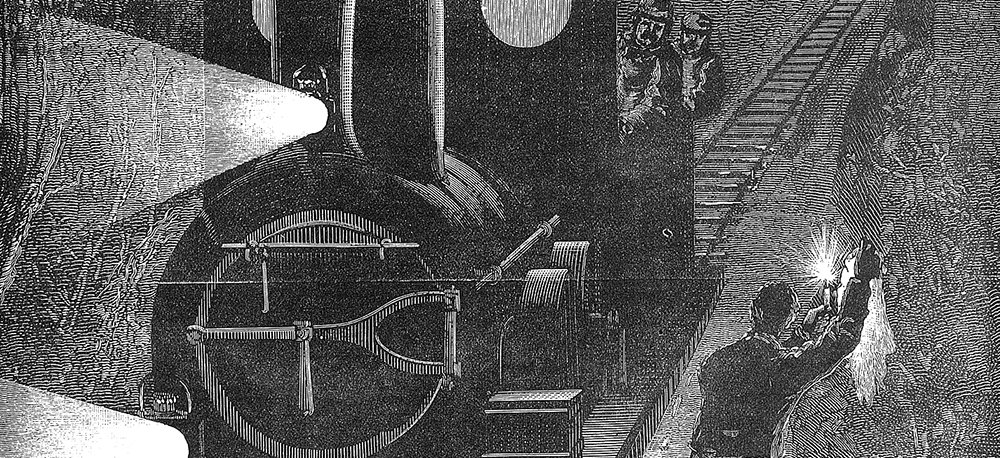

On Saturday, June 27, 1880, the Kelly Gang captured the railway station at Glenrowan. Ned Kelly knew now that the time had come to stand and fight. A crowd of people from the tiny railway town was herded into Mrs Ann Jones’ hotel near the station. Ned suspected that the talkative Mrs Jones was a police spy. Characteristically, he chose her hotel rather than the other one at Glenrowan, McDonnell’s Railway Tavern. in which to make his last stand. With the local policeman, Constable Bracken, having been made prisoner and the telegraph wires cut, the Kelly Gang then preceded to drink with the locals.

On the Sunday afternoon they held a light-hearted ‘sports’ meeting in the hotel yard. Putting aside his guns, Ned competed in a hop, step and jump event, while carrying under his overcoat a full set of armour. There was more drinking but, as evening approached, the Kelly’s decided to cut off Glenrowan more drastically. Ned Kelly ordered a railway fettler by the name of Reardon to tear up a section of the railway track approximately one and a half kilometres north of the station. The plan was to cripple the police special force which the Gang expected to be dispatched from Melbourne, and take the troopers and officials hostage. They would then demand an exchange for a number of prisoners, including Ned’s mother Ellen, and in the process declare the region the Republic of North East Victoria. By then there were more than thirty people crowded into Mrs Jones’ hotel. In the meantime a Police Special, dispatched from Melbourne and full of troopers, reporters, guns and ammunition, was hurtling towards Glenrowan on its way to Wangaratta after being alerted to the Sherritt shooting. The stage was set for the final conflict.

The Shooting Begins

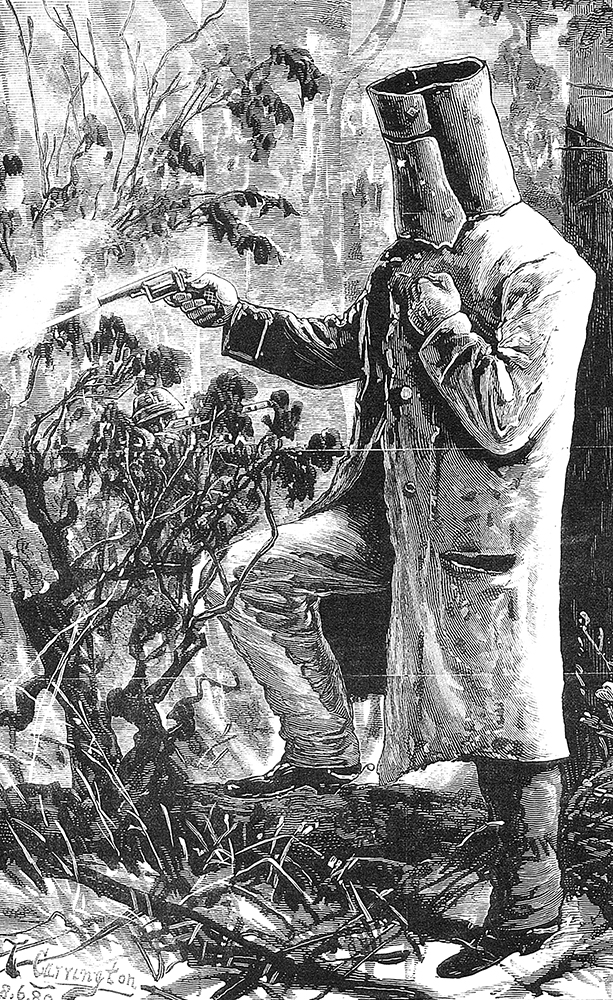

The Kelly’s had not slept for two nights but only the resourceful Constable Bracken and the school teacher, Thomas Curnow, were able to outwit them and escape. A train crowded with police left Melbourne for Kelly Country at 10.15pm that Sunday. In the early hours of next morning the whistle of the approaching train could be heard above the noise in Mrs Jones’ hotel. The Kelly Gang waited for the sound of derailment but it never came. After earlier convincing Ned Kelly to release him, Thomas Curnow, the crippled Glenrowan school teacher, had hobbled around five hundred meters south from the railway station along the track towards Melbourne waving a light shaded in a red cloth shawl he had borrowed from his wife. The train stopped before it reached the rail break, and armed police and native troopers leapt out. Mrs Reardon, imprisoned in the hotel with her children, could hear clanking as Ned Kelly donned his armour in a back room. Hammered out from ploughshares, the armour consisted of a cylindrical helmet, a breastplate with apron and a back plate laced with leather thongs. The armour weighed ninety pounds.

Superintendent Francis Hare, who had been in charge of the Kelly hunt after Euroa until ‘exhaustion’ caused him to pull out, had taken over the pursuit again just before the Glenrowan. At 3am, under bright moonlight, Hare ordered his men to move among the trees and surround the hotel. As they took up firing positions, the Kelly Gang came out and started shooting. In the very first volley Hare was wounded in the forearm by a bullet. He promptly retired to the safety of the post office, leaving some fifty police without a commanding officer.

In the exchange of fire, Joe Byrne was shot in the leg, then he, Dan and Steve retreated into the hotel. Ned Kelly, who was shot in the foot, hand and arm, escaped into the trees to warn the armed sympathisers that their plan to derail the train had failed. During the confusion signal rockets had been fired to alert Ned’s militia. McDonnell’s Railway Tavern stood across from the Glenrowan railway station. It was in front of this hotel where Jack Lloyd mistakenly fired two rockets to rally the sympathisers. The dream of a ‘Republic of North East Victoria’ died with Curnow and the waving of a red scarf.

The women and children pinned inside the Inn were screaming, but the police kept up a murderous rate of gun fire. Dan Kelly ordered the townspeople to lie flat and not to raise their heads. As night faded, the police kept up their barrage while sporadic gunfire emanated from the outlaws’ guns. Inside the hotel, Joe Byrne grabbed a bottle of whiskey, straightened up to drink it and, half way through a toast, dropped dead with a bullet to his groin. John Sadleir writes of Joe’s final scene in the Glenrowan pub, ‘We were told that Byrne had been firing, and was in great spirits, boasting of what the gang was going to do. The work was hot, and he went to the counter for a drink. Finding that the weight of the armour prevented him throwing back his head to swallow the liquor he lifted the apron-shaped plate with one hand while with the other he lifted the glass to his mouth. In this attitude a chance bullet struck him in the groin, and spinning around once he fell dead’. Accounts say that, a moment before the bullet struck Joe Byrne dead, he offered the toast ‘Here’s to the bold Kelly Gang!’ Another report states that he said ‘Many more years in the bush for the Kelly Gang!’ Dawn was breaking. The townspeople, by then almost hysterical, started to brave the police barrage and come out. Mrs Reardon, clutching a shawl round her baby, stepped out from the hotel veranda.

The women roused their little ones and a large party ran out the back door and down the Wangaratta side of the house. They were about to cross the drain close to the gatehouse when a voice from under the culvert cried, “Who comes there?” “Women and children”, they answered. A fusillade of shots passed their faces and they broke and turned and made their way back to the hotel. It was apparent that the police, unused to battle and schooled in dread of the outlaws, would fire in panic at anything on two legs.

Max Brown Australian Son

Mrs Reardon heard a policeman, afterwards identified as Sergeant Steele, call out, ‘Throw up your hands or I’ll shoot you like a bloody dog!’ She ran forward. Steele fired and the bullet passed through the shawl, missing the baby by inches. Two other children were not so lucky. One was wounded and another shot dead, with another youth wounded only a few minutes later.

And then a wail of agony cut through the darkness. It was young Johnny Jones. A police bullet had smashed through the wall and into frail Johnny, just above his hip. Mortally wounded, he screamed for help. ‘Oh, mother! I am shot!’

Paul Terry The True Story of Ned Kelly’s Last Stand

The Bunyip

Sometime before dawn Kelly returned to the hotel, only to see Joe Byrne lying dead. He then appeared outside the hotel and headed into the bush, hoping the surviving Gang members would follow. He then collapsed. Ned has lost much blood, has missed two nights sleep and is still carrying his armour. Here amongst the trees Ned is comforted by his cousin Tom Lloyd. The son of Ned’s uncle Jack Lloyd, Tom Junior was possibly closer to Ned than any member of the gang. Tom was a staunch supporter of Ned and was often referred to as the fifth member of the Kelly Gang. He is recognised today as an important piece of the Kelly puzzle. Tom was friend, adviser, strategist, and tactician to the Gang. During the Kelly uprising, he was a formidable leader of the sympathisers, which led to his arrest. It has been said that in other circumstances he could have been Ned Kelly. Tom and Wild were mainstays of the Kelly Gang but where Isaiah ‘Wild’ Wright was arrogant, Lloyd was far more guarded. When Tom goes to visit Ned in prison prior to his hanging, Kelly tells him where to find a planted saddle. It highlights the bond these two bushmen shared. In later life, Tom became a respected farmer and lived into his seventies.

At this moment he could have escaped, most men would have. Not Ned Kelly. Instead he goes back to rescue his brother and Steve Hart. As the sun rose, out of the ground mist came an apparition limping in dented armour, one arm extended, and his gun in his hand. Senior Constable Kelly was reported to have yelled, ‘He’s the bunyip, boys!’ Bullets rang against Ned’s armour as he walked slowly towards the police front line. A railway guard named Jesse Dowsett stood his ground, firing at Ned Kelly’s legs. Then Senior Constable Kelly, seemingly regaining his wits, also fired at Kelly’s legs as did the trigger-happy Sergeant Steele. Ned at last fell. Within minutes police had surrounded the grotesque figure of the outlaw.

They had to cut the straps to free Ned from his armour. His face was a mask of blood. While Steele declared he alone wounded, unmasked and disarmed Ned Kelly, other men also claimed they helped by wrestling down Ned and hauling off his helmet and armour. Some of those watching Steele’s murderous rage throughout the siege were convinced that he meant to take no prisoners, as Steele had earlier fired at fleeing hostages. Constable Hugh Bracken was quoted as saying, ‘I’ll shoot any bloody man that dares touch him.’ After a remarkable half-hour gunfight and suffering the effects of twenty-eight bullet wounds, Ned was carried into the railway station, close to death. With the sunrise another train had arrived at Glenrowan.

One of its passengers was Father Matthew Gibney, a Roman Catholic priest. Ned Kelly’s sisters, Kate and Maggie, begged Gibney to see their brother and give him the last rites. Father Gibney found the outlaw conscious and administered the sacraments to a critically wounded Ned Kelly. He then went to the hotel. At 3pm, thinking all the townspeople were out, a police constable had crept close and fired the Glenrowan Inn with straw soaked in kerosene which quickly razed the hotel to the ground. Someone cried out that Martin Cherry, a townsman, was trapped inside with the outlaws. So with great courage, Father Gibney went into the blazing building with hands raised high to show he was unarmed. But no shots rang out.

Father Matthew Gibney fought his way through to a back room and there found the lifeless bodies of Dan Kelly and Steve Hart. Giving evidence later at the 1881 Royal Commission, the priest gave it as his opinion that the outlaws had committed suicide, probably by taking poison. The bodies lay side by side, heads propped on folded blankets. Martin Cherry was rescued but later died from a police bullet wound to the groin. The police managed to drag the body of Byrne from the burning Inn moments before the entire building was engulfed in flames while those of Dan Kelly and Steve Hart were charred beyond recognition. Later that day the families claimed both the bodies of Dan and Steve who, after a volatile wake at Eleven Mile Creek, were buried in Greta Cemetery.

Harsh Justice

In only four days Joe Byrne had lost not only his life and that of two Gang members, but had taken the life of his best mate Aaron Sherritt and had also lost the recognition of his mother who refused to claim the body from the Benalla lockup. The same woman who frequently would welcome her son to her Woolshed home during the long nights of the police hunt, right under their very noses. Until recently, Joe was buried in the Benalla cemetery in an unmarked grave, however, today a grave stone marks his final resting place.

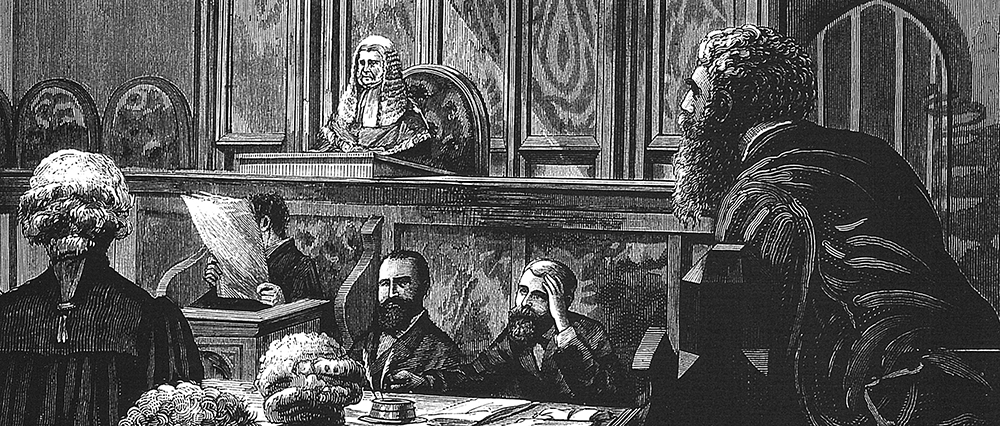

After a Petty Sessions hearing at Beechworth in August, Ned Kelly was taken to Melbourne, passing through streets thronged with gaping people. He was deemed fit to stand trial for murder at Melbourne’s Supreme Court on October 28, 1880. The judge, Sir Redmond Barry, who had once made the grim promise that he would see Ned Kelly hang, wanted to dispose of the trial in a single day, in order to have it finished before the Melbourne Cup. The inexperienced barrister defending Ned was no match for an expert prosecutor, a determined judge and a chief Crown witness — the constable who escaped at Stringybark Creek — and who committed perjury. Barry also misdirected the jury on a vital point of law concerning self-defence. Inevitably, a guilty verdict was announced. Barry sentenced Ned to hang, concluding with: ‘And may the Lord have mercy on your soul.’ Ned famously retorted: ‘I will see you there, where I go.’ Twelve days after Ned was executed, Judge Barry dropped dead in his chambers on November 23, 1880.

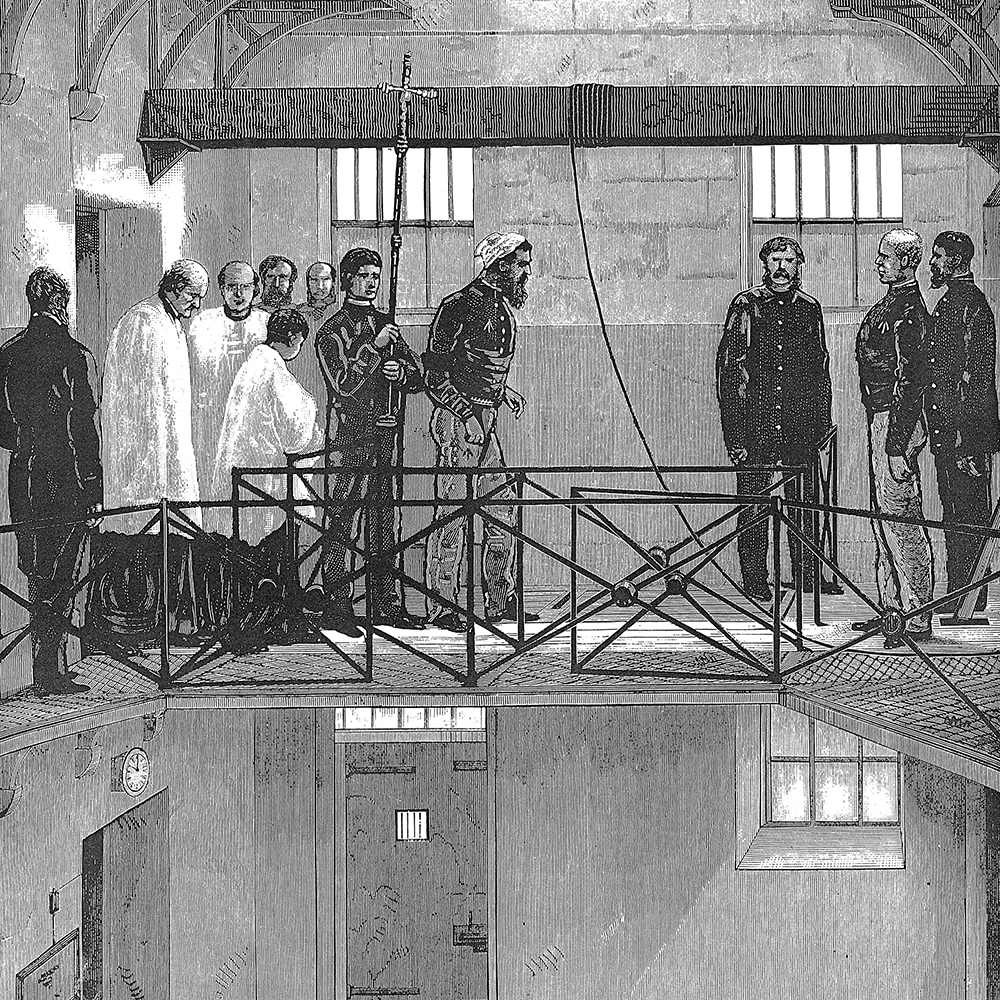

Ned Kelly’s execution was scheduled for Thursday November 11, 1880 — only thirteen days after his trial. A massive movement was launched to save his life. There were huge public meetings, torch-lit marches, a deputation to the Governor, and a petition for Ned’s reprieve from execution. Three days before the planned hanging, the petition was presented to the Governor with more than 32,000 signatures. An hour later, the Executive Council announced that the execution would go ahead.

At 9am on the morning of November 11, as a crowd of five thousand people gathered outside the Melbourne Gaol, Ned was transferred to the condemned cell. Just before 10am, he was led out onto the scaffold. As the hangman, Elijah Upjohn (a transported English convict who was serving a sentence for chicken stealing), adjusted the hood to cover his face, Kelly’s last words were: ‘Arr well, I suppose it has to come to this. Such… (is life?)’. At four minutes past ten, the executioner pulled the lever and Ned Kelly plunged into immortality. His headless body was buried in an unmarked grave on the grounds of the Old Melbourne Gaol. In the 1920s it was then removed to the Pentridge Prison cemetery and, eventually, rested in peace at Great Cemetery with his mother and extended family.

An End and a Beginning

For months after his death, Ned Kelly’s rebellion simmered in North East Victoria, fuelled by the distribution of the £8000 reward money — often referred to as ‘blood money’ by the Gang’s many sympathisers — and the 1881 Royal Commission on the Police Force of Victoria that exposed a number of police spies in Kelly Country. The Commission also found that ‘the incident, however, which seems to have more immediately precipitated the outbreak was the attempt of Constable Fitzpatrick to arrest Dan Kelly, at his mother’s hut, on the 15th of April 1878.’

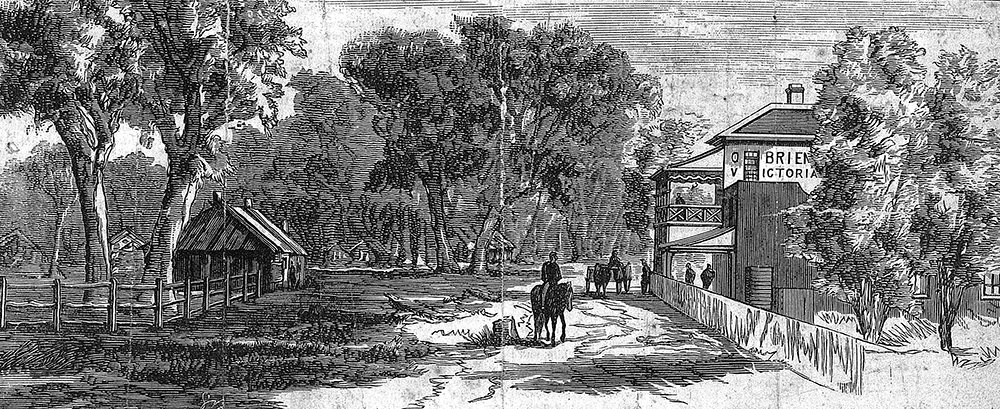

Stationed along with three fellow officers, Senior Constable Robert Graham was entrusted to bring order to a highly volatile situation. For while the police occupied the first floor of O’Brien’s Hotel, Kelly sympathisers swore vengeance in the bar below. Rumour had it new suits of armour were being made. Graham, in charge of the Kelly’s hometown, Greta, traced the root cause of the trouble. It was land. Given an equal right to take up land — and equal justice — the Kelly people quickly subdued the few hotheads bent on violence.

At this juncture, Constable Robert Graham – a young officer contemplating marriage and nicknamed “Honest Bob” – saw an opportunity for conciliation and was allowed to reopen the police station at Greta, which he did – of all venues – in O’Brien’s Hotel. The Glenmore strength was increased meanwhile, and a new station opened in Kiewa valley to block the escape of stolen stock to Gippsland.

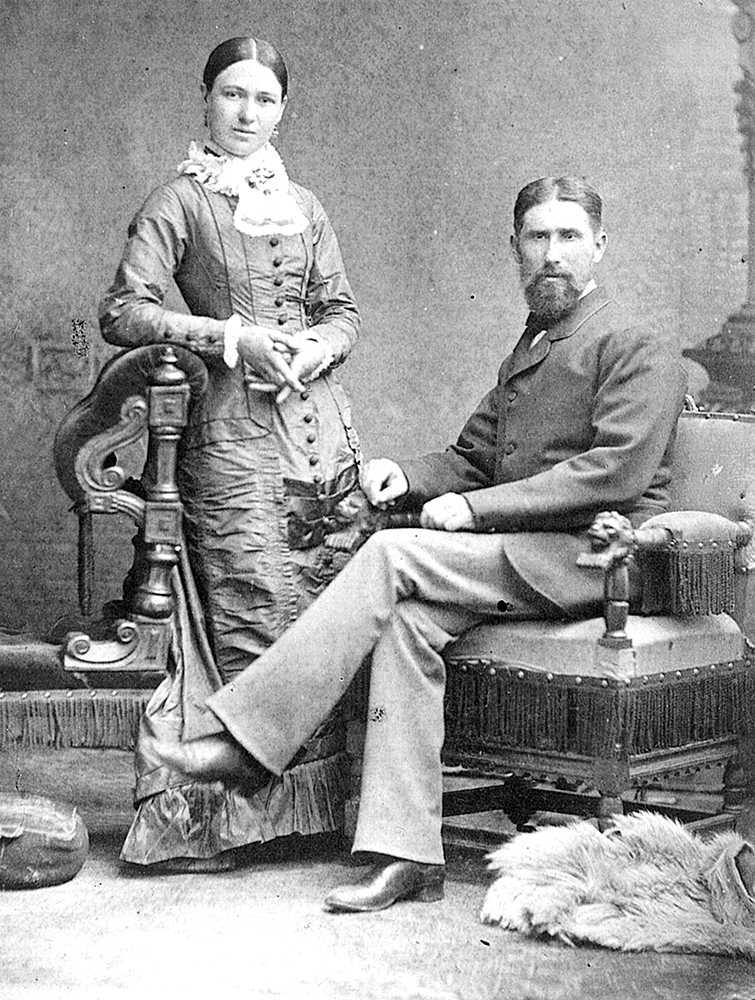

Max Brown Australian Son

Constable Robert Graham, along with his new wife Mary Kirk, managed to gain the trust of Mrs Kelly and her family, and to become a respected member of the community. Ellen Kelly, who died in 1923 at age ninety-one, outlived not only a number of her own children and grandchildren but most of the antagonistic constabulary as well. Supposedly her last words to her son Ned were, ‘Mind you die like a Kelly, son.’